Interview with Tony Harman, Wyeth Ridgway, Chris Albrecht & Joshua Viola

By Krysti Joméi & Jonny DeStefano

Published Issue 108, December 2022

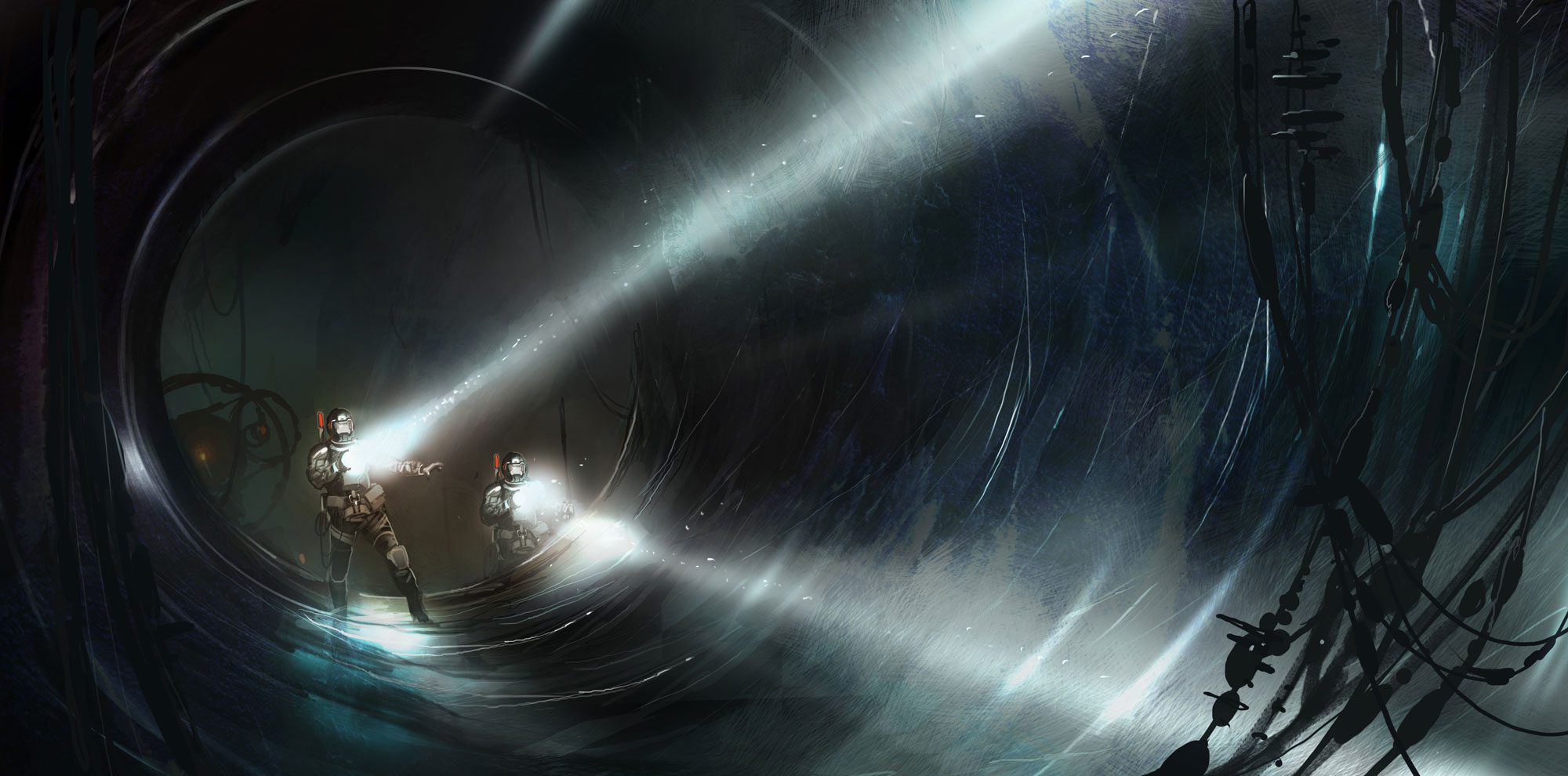

The Unioverse saga begins in the near future when humans have uncovered an ancient technology that can instantly transport your consciousness across the universe. New planets, civilizations, and alien life forms are all connected in the blink of an eye, bringing a deeper meaning to our existence – as well as unforeseen dangers. Who created this technology? What is its true purpose? And will it be our salvation or our ruin?

Launched this year by the spearheading studio, Random Games, a team of gaming and entertainment industry veterans on a mission to empower its community, the Unioverse is not only an epic original sci-fi videogame, but a revolutionary franchise. Community-owned, it reimagines the relationship between developer, gamer and fan through an unheard of model in the industry.

We had the chance to chat with some of the team — Founder/CEO Tony Harman (Donkey Kong Country, Grand Theft Auto), Founder/CTO Wyeth Ridgway (Star Trek, Pirates of the Caribbean), Corporate Communications Chris Albrecht (tech veteran) and Novelization and Comics Creative Director Joshua Viola (Hex Publishers Founder) — about the ever-expanding Unioverse and what this community-owned model will look like.

Krysti Joméi: How was the idea of the Unioverse born?

Tony Harman: Wyeth and I both live in Boulder, Colorado. There’s not a lot of people from the videogame industry in the area so we’ve met for years and wanted to work together. Last summer we started kicking around an idea of a community-owned franchise, but how do you do a community-owned franchise and still generate enough revenue that you can continue to invest in the franchise and grow it? Our aha moment was when a big NFT project called CloneX came out last fall and was able to raise about $100 million, basically it was on a really vague promise: Come buy this PFP little piece of art and we’ll do some fun stuff for you.

All my projects in the past are owned by Nintendo, Microsoft, Sony, Take-Two, so if I’m not going to have any ownership in it, Wyeth and I talked and said, let’s just give it away. Let’s give it all away! Then we came up with the idea that the only way we could pull this off is we have to have something that generates money, so let’s focus on the story and the narrative and bring in some phenomenal talent in writing, art, animation, 3D modeling and put together an awesome team that people would want to support in advance, somewhat like a kickstarter. In exchange for that support we will give them ownership of the assets and let them, if they want to, make T-shirts, lunch boxes, their own comic books. Take our artwork, take our story, take everything and you won’t owe us a single cent of royalty. So it’s basically a great opportunity for people to use some really high quality assets and monetize them themselves.

Jonny DeStefano: Everybody’s so used to corporations ruling everything, but you guys are building community and giving them power back.

Wyeth Ridgway: I’ve spent 20 years making franchise products and it’s very frustrating having to pay Disney up front in order to get access to a franchise. And then you have to submit for approvals for every single little thing you did. So a lot of this vision comes from our frustrations creating movie franchises or also working within them.

One of the things we wanted to do was to be able to offer up to developers everything they need to be successful. In the context of game development that means giving them really high quality assets, giving them a software development kit that works inside the major game engines, giving them an audience which we will go develop upfront and then on top of that, giving them a revenue mechanism where if they entertain our audience we’ll actually pay them. So we’re trying to solve from start to finish all of the problems that there are typical with franchises.

Krysti: When this comes out do you foresee other franchises trying to go this route?

Tony: Yeah, we’re definitely trying to create a model that others can replicate and not just in videogames. One of the top attorneys is working with us to create very unique terms of service, giving the rights for people to use everything that we’re doing — and still secure some rights for us to generate a small amount of revenue off this — to give them a head start to do their own project, to do their own community owned-franchise as well. It’s really important to note that this isn’t a single game. This is a large franchise. You have to think of like Marvel Universe or Star Wars. Those are both owned by Disney. You think Disney is gonna let you make your own comic book and not pay them a royalty? No. But we want to empower creators around the world — there is amazing talent everywhere.

Jonny: We feel the same way with our magazine. Some of the artists and writers that we get who don’t necessarily have a name for themselves are just out of control, so talented.

Wyeth: We would love to watch a lot of people’s careers grow. Where we integrate something that they helped us build and celebrate who they are and then let them take credit for it and let them get into the industry — that is absolutely part of our core vision here.

Krysti: You guys are shattering that scarcity mindset, and that in turn creates a ripple effect of inspiration. Way to do it on a huge level.

Tony: We eventually hope to wake up every morning and check out what people created. For me the vision was initially sparked with Mario Paint years ago. We had an internal tool in Nintendo where people could create artwork and blocks and simple animation, think about old Nintendo Entertainment System days. I thought it was so cool and fun to play with and I go, let’s just bundle this up as a project and give away a bunch of Mario art and see what people can do. A couple of million of those went out and right away there was hundreds of millions of pieces of art that people were showing and submitting and doing videos of and I was blown away by it.

So then the next project was APB and we did a character customization engine and people could make their own characters and gangs or groups of people. And everyday I’d go in there and like the Reservoir Dogs would be running around or a clown group and they painted their cars and it was just phenomenal. It was actually better than what our internal art team did. So if we can create tools to help empower the community and give them some assets — I will not underestimate what the community will deliver.

Krysti: And you’re not only empowering individuals, you’re empowering independent studios of all sizes to build games within the game.

Tony: We only plan to do the initial projects for the initial game. Right now we’re saying we’ll do three projects just to prove the inner operability of our Heroes (avatars) between the different games. But eventually we only want to create Heroes and stories. There’s plenty of great developers out there in the world who we want to utilize our assets.

If you’re a small developer and you’re 6-10 people, you don’t have the ability to build millions of dollars worth of characters — they’re about $100,000-$150,000 each. You have do the concept art. Build the 3D model. You have to rig it. You have to animate it and that adds up. So if you want like eight different characters in your game, you don’t have a million dollars to spend on that. There’s about, last time I looked, 4,000 independent games released per month just on Steam. They can’t possibly get noticed and their budgets for those are far below even what we’re doing for the characters. And on top of that you don’t have the story to put it in. It’s such a disadvantage.

But if you took a sci-fi adventure in Unioverse, and did some offshoot of it, and you had all this lore and you have all this artwork and you have our name, and you have our community who owns these Heroes who are looking for games to drop into — so you don’t need user acquisition — it’s a phenomenal platform for young, independent developers.

Then on top of that, as we stop making games, and they’re making the games as we generate the revenue from the Heroes, we will share half that revenue with these third party developers who are actually out there making content to entertain our community. So we’ll build some initial games and then we really want to continue to build the story and then become mentors and help this young community of indie developers make some awesome content for the Unioverse.

Krysti: I see the incredible team Random Games have procured, but how is this all going to be organized?

Wyeth: Well, the early part of this is we’re just internally building games the same way we’ve done for decades. That’s a very familiar, comfortable and predictable problem. But as we then switch gears to mentoring external companies, we have a bunch of very seasoned, experienced people who will give external teams the opportunities to talk, throw ideas back and forth to us. We actually have a whole lot of engagement in our Discord channels that would be purposed for that sort of thing. But we just become mentors and a support apparatus for the people building stuff inside of Unioverse. We both don’t want to hold them up but we also want to provide them with the tools to make them successful. Ultimately since we build the first set of games, we’ll actually provide them as examples to start with.

Tony: When I was doing a game like Crackdown or APB or Grand Theft Auto those teams swelled to hundreds of people. And it’s a very binary outcome of whether you’re a big success or a catastrophic failure. There’s almost nothing in between. But what we plan to do is sit in the middle and be franchise developers and try the best we can to help create assets, giving away our code, giving away funding to a bunch of small developers. And some of these games will be hit games and get a lot of traction and they’ll be able to step up and create these assets themselves the second time around.

Chris Albrecht: I just want to reinforce what they said: developers can charge whatever they want for a game and keep all the money so they can make it a free-to-play game or they can make it a subscription game or whatever, it just has to include our avatar (Hero). So not only would we pay developers to make these games, they can turn around and sell it for as much as they want and keep all of that money.

Wyeth: That’s unheard of.

Tony: The only money we make is selling Heroes and through their NTFs — they have a smart contract — and the royalties from the smart contract when these Heroes change hands. You have to look at historically what the revenue is for the videogame business. Right now we have an awful situation where Apple, Google and Steam takes 30 percent of your revenue off the top for a transaction. Then they have a crappy store which only a few games are on the front page. So to sell anything you have to work your way up to the front page. The only way you can do that is by paying for user acquisition. So you take half of your revenue and you pay marketing companies to get people to download your game and to play it so you go up the charts. Well now you’ve lost 80 percent of your revenue and that is spun out of the videogame industry to big conglomerates. None of that went to making games better — to the developers.

In our model, screw them all. They make zero from us because we do not sell anything in our games. We have a login, it goes and looks at a wallet, sees what Heroes you own and downloads those Heroes into the game. We do not do any user acquisition. All we care about is our community and making content for our community. So what do we need to survive? We don’t have to pay Apple, Google or Steam, we don’t have to pay user acquisition companies — not only is that enough money for us to survive, it’s enough money for us to give grants out to third party developers to make content as well for Unioverse.

Jonny: When you’re investing back into these people who really care about it, have passion for it, you’re going to have better quality.

Tony: Also, if you set out to make a game, I’m sure you can make a fun game if you made it for something that you love. But the problem is that you and other developers don’t have the business analytics skills for a free-to-play game. And the whole industry went to free-to-play. You only collect money on average from 1-3 percent of your users who convert to paid users. But you have to pay for servers for 100 percent of them. So then you have to extract as much money as you can out of that 1-3 percent, so you completely warp your game concept and have to create things that pull more and more money out of that 1-3 percent. With our particular model, our games that we’re doing ourselves are just free. We just focus on making fun games. Our community can do whatever they want.

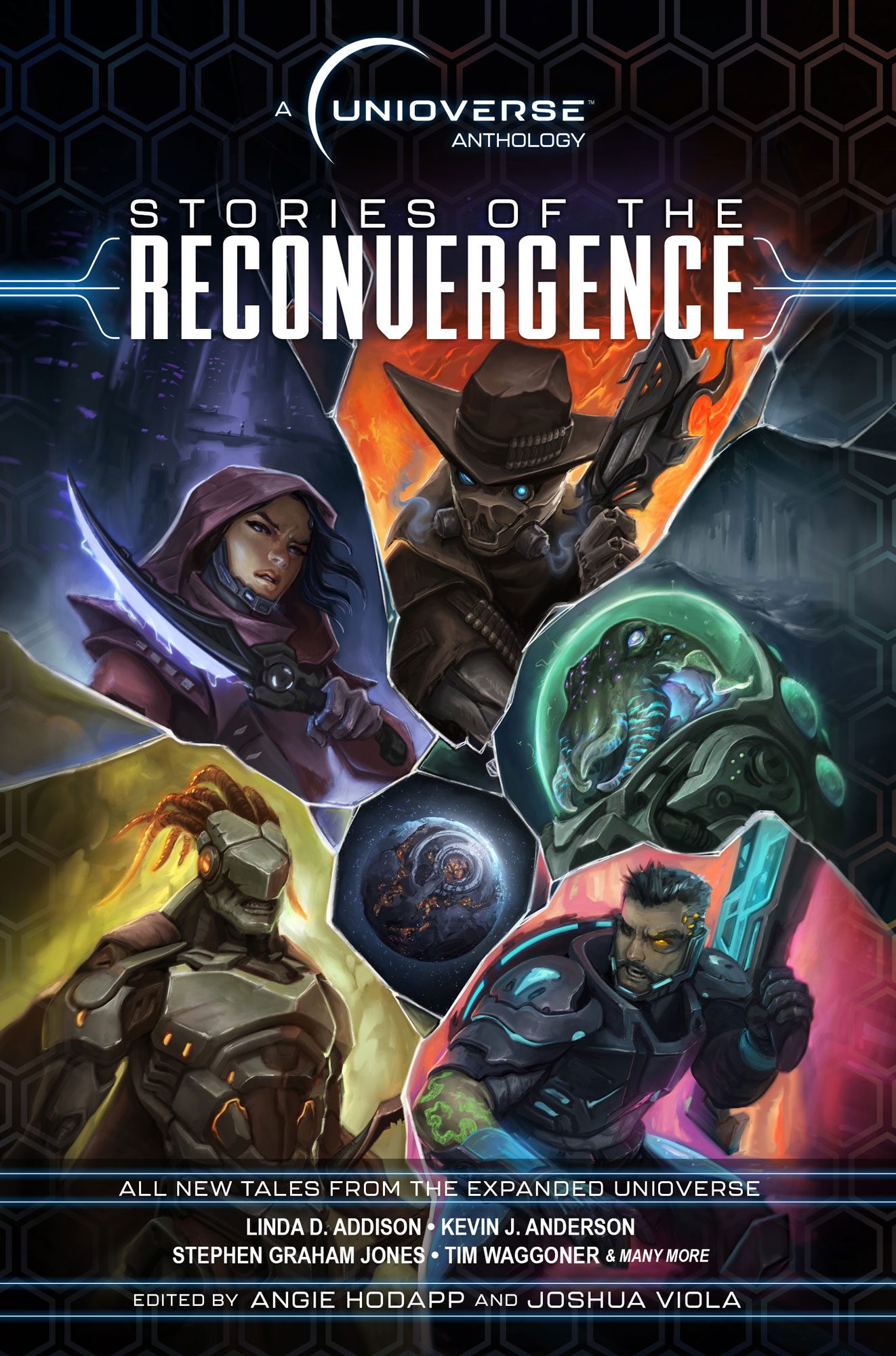

Chris: I wonder if it would help for the visual of the game if we could tell the story of the Unioverse and maybe Josh can talk about the anthology (Stories of the Reconvergence).

Wyeth: So this is a game first franchise and the way that I describe that is there are dozens and dozens of top franchises out there, and some of those franchises are not really friendly to making games — because no one who was making games was involved early on. One of the examples I give is Mr. Stretch from the Fantastic Four. You can draw him and he looks really interesting but he’s just a nightmare from a gameplay perspective — very difficult to control and he’s got open-ended abilities. So when I say we’re making a game first franchise it’s really about saying we want to make a sci-fi world, and we want it to be easy and rewarding and very inviting for game developers to come and build games inside of.

The other things that we set out to do early on was come up with a way to link a whole bunch of different worlds so there could be so many different stories but through a very unique mechanism — through this idea that there’s no faster than light travel through the Unioverse. Pretty much every sci-fi, distant future thing you can think of, people just have this caveat of you can just instantly travel anywhere. That’s not how our universe works at all. If you want to go to Mars, it’s an eight month trip. And on top of that we layered in this notion that a race from millions of years ago came up with a way to let people navigate around the universe through sending consciousness through time and space — into another body. And that was developed heavily by Brent Friedman, one of our main world building architects, and then we turned that around with some rules that we gave to Josh to build stories with it.

Joshua Viola: The elevator pitch of how I’ve sorta framed Unioverse is Game of Thrones meets Altered Carbon meets Dune and beyond in a richly imagined universe where all sentient life from a vast network of far-flung planets is connected by instantaneous intergalactic travel. When I first came on to the team in the spring, I communicated with Wyeth and Brent to get a loose understanding of the world, knowing we were going to be building anthologies by taking this information that they’ve developed and turning them into stories and recruiting authors to help us do that. I actually wrote a story myself to kind of kickstart it and through that process we actually discovered many plot holes and things that needed to be fixed. That was a unique process because then we went back to the drawing board and we set a hard deadline for patching those holes. That’s when we recruited some other people to help establish us further. Now we have this massive Wiki that all of the writers can access. And it’s constantly evolving and growing. Not only are they telling their own short stories, they’re actually helping evolve the Unioverse and that’s been a really neat collaborative process.

Brent Friedman, Andy Baker, Angie Hodapp and myself are going back and forth with the writers to get it to a nice final pristine place. Stu Jennett will be developing an actual piece of story art for each story that’s included inside the book. Aaron Lovett did the cover art and additionally from the story telling side of things, Angie and I are cowriting the comic book series which is sort of the introduction to some of the established main Heroes that exist right now. We hired a phenomenal artist, Ben Matsuya, who’s doing the interior art and we have a variety of cover artists that are contributing. We’ve got Tyler Kirkham (Marvel, DC). And then AJ Nazzaro (Blizzard Entertainment), he’s doing the main cover. The comic books are really cool because we’re also introducing the villain.

Krysti: Knowing your anthologies I know the writers involved are going to be amazing too.

Josh: Thank you. Stephen Graham Jones is in it. Kevin J. Anderson, he’s the author of the Dune and a Star Wars series among many other things. Linda D. Addison, she was just in the most recent Predator anthology tie-in to that new movie. And then a lot of established writers that have existed in Hex anthologies. We’re also including poetry — and this prose poetry is phenomenal.

Chris: What other questions can we answer for you here?

Krysti: I think fun questions are really important.

Chris: Fun away!

Krysti: What’s your favorite OG video game and/or what’s currently in your system?

Tony: I’ve played more old school ones. I still every year with my kids break out Zelda and Metroid. And I do it for a specific reason. We go buy graph paper or we make some on the computer and print it out and then we map out the worlds and the dungeons and try to find the hidden stuff again. And I guess I’m getting older because I forget them all every year so it’s new entertainment for me every year.

Wyeth: I’m gonna take an old school arcade game: Dungeons & Dragons: Shadows over Mystara — a character-based side-scroller but you could create an account on the arcade game — nobody did this — and then you come back and keep playing the same character and it progressed in level. It was just so far ahead of its time, it was amazing.

Chris: Yars’ Revenge on the Atari 2600 I spent a lot of time playing that. But the one I’m playing a lot right now with friends is Prodeus. If you played Castle Wolfenstein in the 90s it is a phenomenal recreation of that style of game. My son looks at it and is like, why is it all pixilated? Well, that doesn’t look any good. (laughs) It’s one of the most fluid and best gaming experiences I’ve had in a long time and the multiplayer is a lot of fun.

Josh: I’m not going to go super OG on mine but I would say it’s a three-way tie between Ocarina of Time, the original Halo and Soul Reaver. And then in my Playstation I have Stray. The other one I’m playing is the Last of Us remake which is awesome. My friend Colleen Larson was one of the lead character artists on the new version — Real quick (before we leave), tell them what you told me about Kirby, Tony, that was just awesome.

Tony: Well I’ve named more Nintendo games then anyone I’m sure. But — Mr. Iwata became president of Nintendo, he was a developer at HAL Laboratory at the time and he and Mr. Miyamoto were showing me the Kirby character and they couldn’t come up with a name for it. He was like he’s just kind of like a vacuum, and I said you know, there’s a manufacturer of vacuums called Kirby in the U.S. and so that became his name. (laughs) And like F-Zero — we’re sitting on a bullet train and he was like these cars are faster, what are the names of race circuits, tracks and races? I was like, oh Formula 1, Formula 3. And Miyamoto is like what about Formula 2? And I go, there’s no Formula 2. It just goes from Formula 1 to Formula 3. And he goes which one is better? It goes backwards, 1 is better than 3. And he’s like, well then what’s better than 1? And I’m like, well how about 0? And that’s how F-Zero was named on this bullet train ride trying to explain racing.

Jonny: That’s so cool.

Chris: Well, thank you both so much and thank you everyone for taking the time to talk.

Learn more and stay up to date on all things Unioverse on their site | Follow them on Twitter & Join their Discord