Grandmother Releases Her Ward

By Joel Tagert

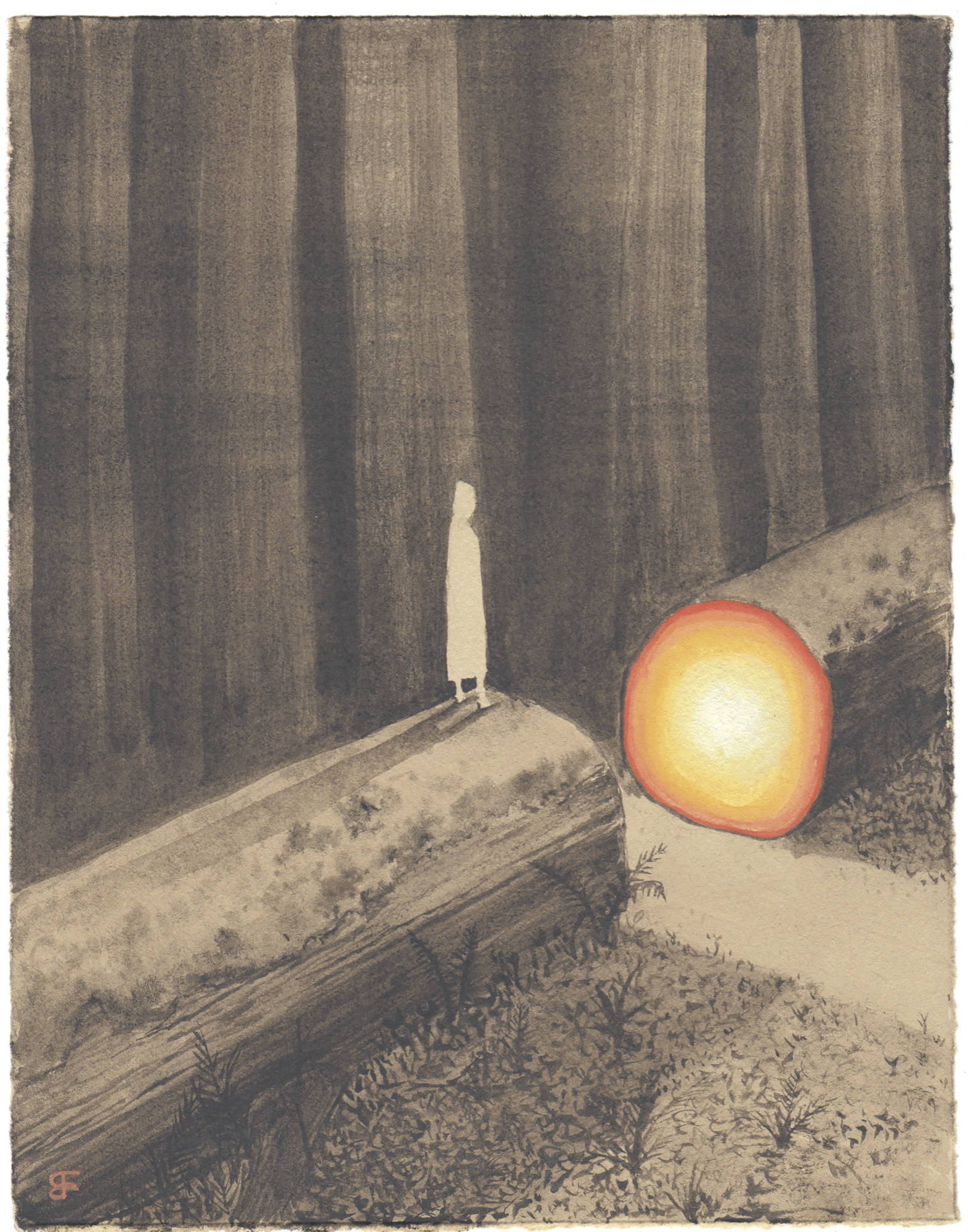

Art by Graham Franciose

Published Issue 090, June 2021

Yehl tried to find a time when Grandmother was alone, but this was rare, and so despite his efforts her eldest daughter was there also in the longhouse. After making a gift of a small clay pot of black currant jam, he began, “Naadkym is of age today.”

Grandmother nodded. “A fine boy. He reminds me every day of his father. Tall and strong.”

“A fine man, now.”

“Yes, of course. Though you all look like children to me.”

That’s part of the problem. “He is a man,” Yehl pressed on, “but who will he marry, Grandmother?”

The old woman’s lips pursed. “Nuwu, perhaps …”

“Nuwu is a toddler. She just learned to walk.”

“Yasa, then.”

“Yasateji is already betrothed to Xetsuwu.”

Grandmother shook her head. “Let me think on this, Yehl. I’m tired today.”

Yehl thrust out his chin. “There’s no one. No girl even close to his age who isn’t already married. And there weren’t many to begin with.”

She scoffed. “Well, what can I do? Carve you one out of cedar?”

“You can lift the ward on the village.”

Grandmother rocked back on her cushion. Her daughter stopped her weaving and stared, astonished. “Can you do that?” the middle-aged woman spoke, addressing her mother.

Grandmother shook her head. “Nonsense. Grandfather Turtle chose to protect our village because of our devotion to him. What can one old woman do?”

“One old woman who made the spell in the first place could do a lot, maybe,” Yehl argued. “I saw with my own eyes how you marked the poles, when I was just a boy. It was you that closed the village, and I think you can open it.”

“And why would I?” she responded querulously. “You saw me mark the poles, but you didn’t see my journey just before. I went to give medicine, and instead I found death. Village after village burning with fever, their skin bursting with blisters, and what few remained rounded up and enslaved. Yet here we are, alive and well, with pots of berry jam, no less! Strong!”

“Alive, yes, strong, maybe, but it can’t last, Grandmother. Place a fish in a puddle and it lives for a while, and then dies. Maybe it dies of loneliness.”

Still she shook her head. “You didn’t see,” she whispered. “We would have died.”

“Yes, but we didn’t. Now we have to live.”

For a long time they were silent, heads bowed in thought. “It’s too much risk for everybody,” she said finally. “If you’re set on this, then you go alone. Return only if you’re certain it’s safe.”

A sudden fear struck him. He didn’t doubt her sincerity; he could die like those others. But almost immediately his trepidation was countered by a great burst of curiosity. What was out there? “Yes, all right. I agree.”

“Come back tomorrow at sunset,” she said, “prepared for a journey.”

“Can I go by canoe?”

She shook her head. “To pass the ward, you must go on foot.”

At the appointed time she smeared a truly foul-smelling paste on his forehead (he suspected otter shit) and stood chanting for some time while they stood at the two poles that marked the village’s eastern edge. Most of the village, fifty or so people, had come out to watch in the slanting light. Her chanting ended in a wail, then abrupt silence. She nodded east and he turned to go.

He had gone this direction many times, of course, as they all had, and every other direction beside. If you went by canoe, the current drove you back to the bay. On foot, you would reach a certain point and become confused, until you found you had turned and were walking back to the village. Clearly outsiders encountered similar obstacles, for the village had not seen a visitor in thirty-three years.

But tonight his head was clear, nostrils full of the acrid stink of the paste. He walked down the trail with the sun at his back. At one point he had to climb over a great fir that had fallen across the path; then he was in wilderness.

It was Naadkym who spotted him first on his return. This was not entirely coincidence, for the young man had made a habit of sitting in a certain spot near the storehouse where he had a view of the trail. When he spotted the newcomer, arriving in late afternoon, he stood up in astonishment.

He did not recognize his uncle at first. His hair was cut differently, and he wore pieces of mirrored glass, like abalone shells, in front of his eyes. The rest of his apparel was like nothing Naadkym had seen before: blue leggings, a checked red shirt, tough-looking boots. “Hey!” the teenager said finally.

The stranger turned. “Nephew,” he said, and that’s when it fell into place. “Uncle!” he yelled, and ran to greet him properly.

Examined more closely, he saw that Yehl had changed in less obvious ways also. He seemed … older, with new lines in his face. This was confirmed in an unexpected way when Yehl asked, “How long have I been gone?”

The young man was puzzled. “Six months, I think.”

Yehl shook his head, looking worn. “That’s what I thought. Grandmother’s spell really is powerful. To me, I’ve been gone three years. The whole village, then … ” His eyes went distant with calculation. “Two hundred years vanished, more or less.”

“But what’s out there?”

He sighed. “Let’s go see Grandmother.”

“Okay. But you should know, she’s sick.”

Three years for him, three months for her: but here the old woman lay in her blankets. She peered up at him and the crowded longhouse with rheumy eyes. “Yehl,” she breathed finally, nearly whispering. “Is it safe?”

“No,” he said thoughtfully, “not really safe. But safe enough.”

“The pox?”

“Gone. Completely.”

“Ahhh.” She lifted a trembling hand and patted his cheek. “It’s time, then.”

She died before sunrise. He had little doubt that her spell passed with her. After the funeral, he took Naadkym aside. “Come with me.”

They hiked east again along the path, until they reached the giant fir blocking it. On the other side, Naadkym’s eyes widened, seeing the vehicle there. He had no words to describe it. “It’s called a truck,” his uncle said. “And the next thing I’m going to show you is called a chainsaw.”

It was hard, hard labor cutting even a narrow gap through the tree, the saw screaming and spitting dust. By the time it was over, well past dusk, Naadkym had learned how to drive and open apps on his uncle’s iPhone. He also had a furious headache, but this new world was one of absolute wonder. “Is it all like this?” he said, holding the phone aloft.

“No,” his uncle said. “It’s more like … that chainsaw. Great, unless you’re the tree.”

Joel Tagert is a fiction writer, artist and longtime Zen practitioner living in Denver, Colorado. He is also currently the office manager for the Zen Center of Denver and the editorial proofreader for Westword. His debut novel, INFERENCE, was released July 2017.

Graham Franciose grew up in the forests of Massachusetts. His work reaches back to those times of exploration and imagination, where anything was possible. His whimsical, sometimes emotional, illustrations show a sliver of a story, a moment between the action, leaving the exact circumstances and narrative up to the viewer. There is sense of familiarity and honesty within his characters and scenes, as well as a sense of mystery and wonder. He currently lives and works as a professional artist and illustrator in Austin, TX. See more of his work on his site and follow him on Instagram.