The Artist In The Flesh

By Joel Tagert

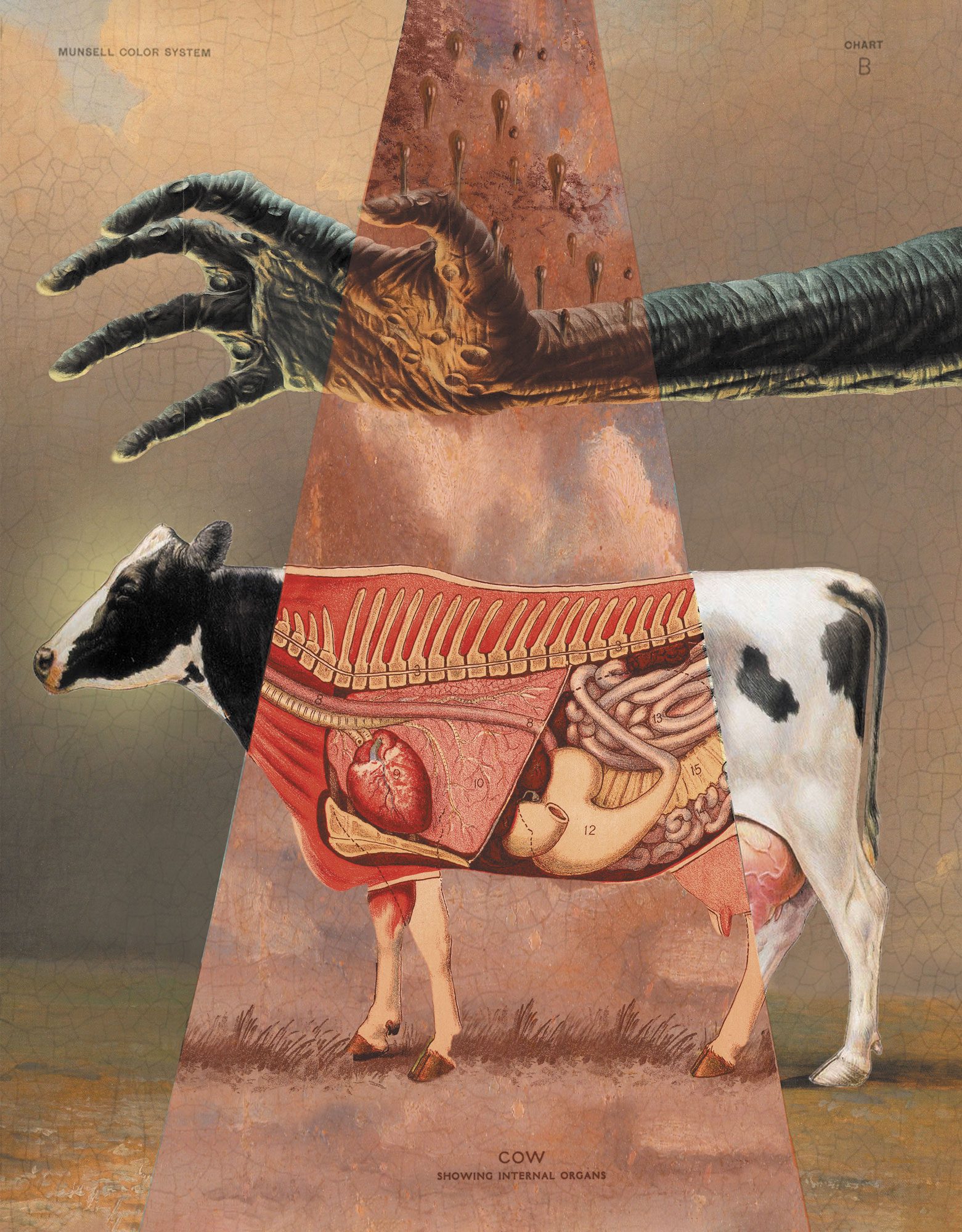

Art by Moon_Patrol

Published Issue 106, October 2022

The steer had been flayed and dissected, its skin, organs and bones arranged upon the shrubland in a meticulous mandala with the animal’s heart at its center, a cloud of black flies fighting the Wyoming wind to claim their share of the bounty. Dick Gerlits stalked slowly around the circle — fifty feet from edge to edge — a scowl steadily cutting deeper into his leathered features.

“What do you think, boss?” asked Hector.

Gerlits took his time answering. “I think I’m gonna find the son of a bitch that did this and nail his fucking hide to my wall. If it’s the last thing I do in this life, I’m gonna find him.”

“Well, watch out if you do,” said JJ. “Cause this son of a bitch has got a sharp knife.”

“That supposed to be a joke?”

“I ain’t laughing. But look at it. He knew what he was doing.”

Gerlits nodded, eyes tracing the calligraphic loops of intestines, the runic ribs. “No blood.”

“Huh. Must have drained it first. Then what, they take it with ’em? Do a little prom scene with it later?”

This was his animal. Done on his land. “I’ll ask when I find him.”

“But who?” said Hector, baffled.

∆

That was the million-dollar question. The sheriff’s office didn’t have shit to say about it, no surprise with that twit Dollard at the reins. Everybody had a theory, but none of them made much sense. JJ was convinced it was some druggies, out of their heads on meth. Hector told credulous stories of chupacabra. Dick’s wife, June, said it was Satanists up from Denver: she’d seen one the night before at the Flying J, a goat’s head tattooed on his neck, if you could believe it. Gerlits brooded on past wrongs and old enemies.

But there were no leads, nothing concrete. Not even any tracks close to the scene. Half the people in town thought it was someone at the ranch, a notion Gerlits had entertained himself before finally crossing each of his half-dozen employees off the list.

At week’s end he went online and spent three grand on eight network-connected trail cameras. Recognizing that this wouldn’t be enough to capture even a small fraction of the twelve-hundred acre ranch, he placed four on fenceposts near the hill where they’d found the steer. The rest he situated at road entrances and turnoffs, reasoning that missing tire tracks aside, the bastards hadn’t walked out there. It was October before it happened again.

∆

Gerlits found the cow himself this time, half a mile west of where they’d discovered the dismantled steer, in the meadow just shy of where the cottonwoods rose near the Platte. Even before that grisly find he’d often driven around the ranch, keeping a watch on things, but since then he’d made a point of circling the roads morning and evening. So he found it with the rising sun still low, the air crisp but the wind faint, what June would call a blessing of a day.

This time the perpetrator had set the bones in an equilateral triangle pointing directly north, the intestines winding in a filigree around the edges, the organs arrayed by shade — dark to light — in the interior, with the cow’s skull at the apex, the eyes, tongue and ears set in perfect symmetry on either side of the still-intact spinal cord, leading up to the brain in the opened bone casing. The fatty folds glistened in the golden dawn light.

“Show-off,” Gerlits muttered.

∆

The time stamp on the video read 3:56 a.m. That alone was surprising; he’d assumed it would take all night to undertake such complex work. The cow ambled into frame, reading pretty small; the camera had a lot of pixels, but the animal was still too distant for good detail.

Suddenly a cone of light flashed on: flashed on from above, like a streetlight, its source out of frame. The image flared as the camera tried to adjust, with only partial success. It would stay washed-out no matter how he played with it.

Then the cow rose into the air: or at least, that was how it looked on his screen. It was kicking and bucking, clearly panicked, but it bucked in place, as though on a hoist (and maybe it was on a hoist). Its black shadow began to grow tangled and unreasonable, warping and stretching. Lines and shapes erupted from it, twisting and curving until they drifted to the wheatgrass below. Steadily the bulk of the cow diminished until there was nothing left. The light snapped off, and with the motion stilled, the camera shut off too.

For hours Gerlits played and replayed the video, zooming in and out, altering filters and settings. When all that proved to offer few insights, he stared off at the shelves of his study, where he’d set some of the smaller animals he’d caught and stuffed over the years: rattlesnake, barn owl, fox. Their frozen visages returned his gaze with hatred and fear, silently hissing, hooting and snarling.

∆

“I’m starting to think you got some sweetheart in town.”

“Don’t say that. You know where I am.”

“You get up in the middle of the night and disappear. You don’t come back until dawn and then sleep half the day. You’ve never been like this.”

“You saw the video. You saw what they did to our cows.”

Since the recording Gerlits had built a hunter’s blind, camouflaged as completely as he could manage. For weeks he had spent most of his nights hidden there, waiting with a pair of night-vision binoculars and a Browning long-range rifle.

“Maybe it’s …” June trailed off. “I just want to know where you are.”

“I’m out at the blind. That’s all.”

“In the cold?”

“Yes, in the cold.”

“Well, just make sure you keep your clothes on,” she said.

Gerlits pushed back his chair and stood up from the table. “Where you going?” his wife said.

“Out to the shed.”

“You haven’t even finished your steak.”

“Lost my appetite.”

∆

Weeks in the grass-topped shelter, half-huddled in a sleeping bag, listening to the wind whistle and howl, waiting for a light from the sky. June might be able to ignore it, tell herself it was God or Satan, but he couldn’t. Something was out here, on his land. It was his.

∆

He was half-dozing when a light flashed in his eyes. His first thought: Someone driving on the highway. Then he woke up fully, adrenaline surging. There wasn’t a road in that direction. He snatched up the binoculars. A cow was lowing loudly, beneath its cries a powerful throbbing hum.

Where the camera had failed, the binoculars rendered everything in exquisite detail. The cow was lifted right into the open air and peeled apart like an orange. It was still hard to see what was doing it, but it was dark and round, floating absolutely steady in the air above the scrubland. Maybe as wide as a house trailer was long. It seemed to be etched all over its surface, like a cuneiform tablet, and it had an opening or hole on its underside from which the light shone.

Not a drop of blood reached the ground. Instead the fluid floated in the air, forming a red cloud, until the cow’s disintegrating body was suspended inside a crimson snowglobe. When the final gobbets of flesh drifted down to the earth, still the blood hung there.

Something descended from the vessel. It was humanoid, but long-limbed, big-headed. It was facing away from him. It levitated downward, into the red mist.

The globule shrunk inward. It flowed into the creature’s skin until all that remained was a crimson silhouette with long-fingered arms extended at its sides, like a withered child dipped in red paint.

The rifle, you idiot!

He set down the binoculars and scrabbled for the gun, but by the time he brought up the sight it was too late. The ship, and its owner, were gone.

Maybe it was for the best. It had visited three times. It must like this hunting ground, this canvas. He thought there was a good chance it would come back.

The remains were hexiform, three crossed lines of skin cut like tank tracks, with the ribs stuck vertically in the earth around them. It was like a shrine. He felt he was on hallowed ground.

∆

It took so long for the visitor to return that Gerlits was afraid he’d missed his chance. All through the brutal Wyoming winter he shivered in his blind. June thought he’d gone crazy; she went to stay with her sister in Sheridan. He gave Hector authority over the ranch’s day-to-day operations, which pleased Hector but made JJ quit in a pique. Gerlits could give a shit. He was on the hunt. He drank black coffee and hot soup from two thermoses, bought boxes of chemical heat packs.

He performed his other preparations in the padlocked steel shed down the road from the house, where he kept works in progress, along with his experiments, taxidermies he wouldn’t want seen, and videos of how he’d made them. He thought of burning the lot sometimes, but the locks were sturdy and he couldn’t part with them. Along with his knives and needles, he had a reasonable supply of veterinary supplies, including a dart gun and some ketamine. These he moved to the hunting blind early on.

He kept most of the cattle in the lot at night, but he would let a few out strategically, tracking their progress. One glorious, freezing March night, with the snow drifting against the breaks, it paid off.

He heard the humming first, the sound he’d been waiting for. He raised the dart gun to his shoulder. He’d already been following the cow’s progress across the fields; the animal was no doubt desperate to huddle into the herd. He didn’t wait for further activity, but fired, loaded again, fired, loaded, fired.

The dissection was beautiful. Gerlits was like a spectator in an operating theater, a baseball fan at the game, a season ticket holder at the opera. When the show concluded, he held his breath as the master descended from his perch to drink a cup of wine.

The alien hung there, red and glistening. Ecstatic. Then it shuddered. It fell. The light from the ship flicked off.

Gerlits turned the gun and scope to the side, stared into the darkness with his unaided eyes. Then he clicked on his head lamp and scuttled out of the blind to run into the biting cold.

The remnants of the carcass were arranged in stippled piles, at least a hundred of them, a delicate sunflower pattern dabbed in muscle and bone. The creature that had made them lay upon his work barely moving. It had long, thin limbs, a huge triangular head, no mouth, a slitted nose, mantis eyes. While a second before its whole body had been crimson with stolen blood, now its wrinkled, mottled skin was rapidly darkening to near-black. No smooth-skinned babe this: it looked ancient as a mummy.

He had worried there might be more of them in the ship, but inwardly he was convinced the thing was alone, and as he crouched between the cow’s remains, that conviction seemed to be borne out. He looked around the circle once more, with admiration, then returned his attention to the alien.

“You extract the blood because you need it,” he said. “Or maybe just cause you like it. But you make the design just for fun, don’t you? A work of art.” Carefully he unsheathed the skinning knife at his hip, turning the curved steel talon to catch the beam from his head light, snowflakes whirling. “I’m a bit of an artist myself.”

Joel Tagert is a fiction writer and artist, the author of INFERENCE, and a longtime Zen practitioner living in Denver, Colorado. He is also currently the office manager for the Zen Center of Denver and the editorial proofreader for Westword.

Moon Patrol is a Northern California-based artist. Taking themes including ’80s cartoons and video games, classic pulp illustrations, and comic book narratives, Moon Patrol remixes these many and varied cues using a collage technique he compares to “Kid Koala’s turntable albums, and in part by William Burroughs’ cut-up technique.” See more of his work on Instagram and snag prints at Outré Gallery.

Check out Joel’s September Birdy install, The Widow’s Pilgrimage, and Moon_Patrol’s, Garden Dragon, or head to our Explore section to see more from these creatives.