The Sleeper

By Joel Tagert

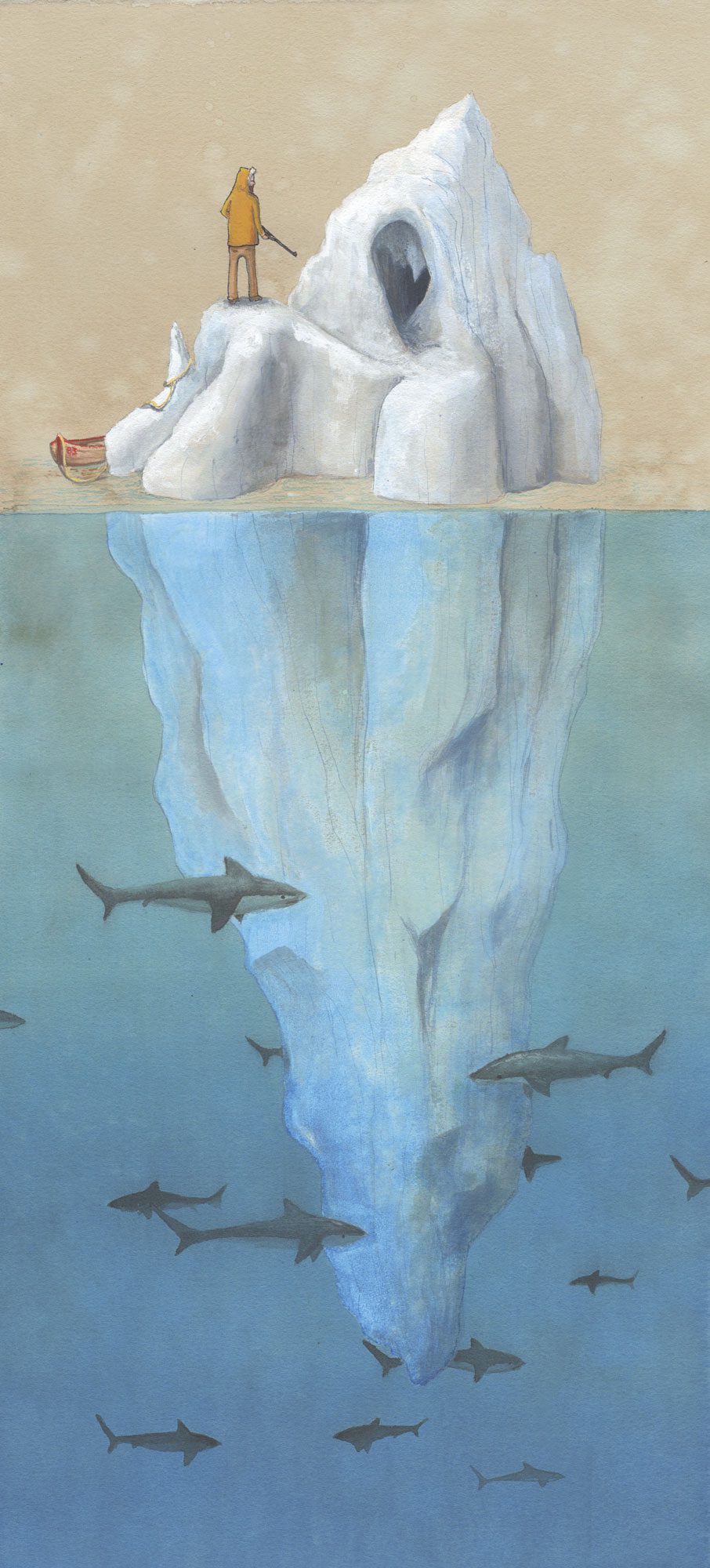

Art by Graham Franciose

Published Issue 144, December 2025

Best of Birdy, Originally Published Issue 108, December 2022

At other Arctic villages the Felix and its crew had been variously greeted with astonishment, alarm or hostility, to be expected in places where the inhabitants had never seen Europeans, much less a schooner. But when Captain John Ross and five other men disembarked from the jolly boat at that unnamed hamlet in Lancaster Sound — so far as anyone knew, the northernmost settlement in the world — they were greeted only by a delegation of four village elders, who through gestures and Felix’s translator, Minik, indicated they would prefer that their visitors be on their way.

“Do they have any berries?” asked Hugh McCollough, the ship’s surgeon, much concerned with scurvy. “Edible plants of any kind?”

“We’ll get to that,” Ross said. “Ask if they’ve seen any ships.”

Yes: one ship, its men in even worse condition, late the previous summer. Clearly the villagers had unhappy memories of their stay. Ross withdrew an oiled leather tube from within his greatcoat and carefully slipped out a sheet of paper, which he unrolled and held up for the natives’ inspection. Now came the astonishment, the loud excited talking. One of them tried to touch it, but Cort Rainick, the second mate, slapped away the man’s hand. “They recognize him,” Ross said triumphantly.

“No,” said Minik. “They’ve just never seen a portrait before.” Ross scowled. “Did the other sailors leave anything? Any sign, any writing?”

Minik asked, and one of the elders, a tiny, wrinkled old woman, waved at them to follow her. They walked upslope through the village, the residents emerging from a dozen sealskin tents to stare while a pack of thickly furred dogs barked and snapped at the newcomers, fended off by the

sailors wielding the butts of their rifles. Thirty yards beyond the last tent they stopped before a small cairn set with a crude driftwood cross. “Not even a name,” Ross said in disgust.

“There might be identifi ers on the body,” suggested McCullough. “A uniform, even.”

“Fucking ghoul,” muttered one of the sailors.

“It’s just a body.”

“It’s his immortal soul,” protested Rainick, more religious than he appeared.

“His immortal soul, if indeed he ever had one, is long fled. What’s under these stones is a corpse.”

Ross was torn. He was a religious man himself and hated to disturb the sanctity of a Christian burial; also the men would hate it, call it bad luck (the cynical McCullough aside), and they were already unhappy with this long, cold, hungry voyage. At the same time, if there was any indication of the man’s identity — if they could ascertain he was from the Erebus or Terror — it would be the first real clue to the fate of the missing ships. Fortunately he was saved from giving the order by Minik, who had continued questioning the old woman while the Europeans debated “There was another man left here,” said the Greenlander. “Not dead.”

“Alive, then?” asked Ross.

“He was. But he was very sick.”

“‘Was, was.’ Is he here or not? Alive or dead?”

“She says … not alive, not dead. Sleeping.”

“Devil take you, is the man here alive in the village or not? Do we have to search the place?”

“Sorry, Captain, their dialect is different than I’m used to. She says he’s… with Anguta.”

“Which is what? A person?”

Minik looked troubled, and spent several minutes in dialogue while the sailors waited impatiently. Finally he said, “I think a person, aye. Anguta is their god, who takes the spirit down to Adlivun, where the dead go. So at first I thought maybe she was just saying he was dead, like a poetic expression, you know? But now I think she means a real person, angakkuq, a holy man. They brought him to be healed.”

“And where do we find this holy man?”

“In a cave, an ice cave north on the coast. She says her husband can take us there, but Anguta won’t speak to us unless we bring him a shark for an offering.”

“Pagh.” More time wasted. “Tell her to get her husband.”

***

Not any kind of shark would do, however: the woman’s husband, named Saki, described one large, slow moving, full of oil. “He means a sleeper,” said one of the hands, Malachai Stevens, who like half the crew had been a whaler. “Some call it a Greenland shark.”

“Can you catch one?” asked Ross.

“Oh aye, easy enough. They swim deep and slow, but toss out some bait and they’ll come like any other shark. Meat’s no good — will turn your limbs asleep if you eat too much — but we fish ’em for the oil.”

By the next afternoon they had their shark — an ancient monster with eyes like silver coins, a mouth like the yawning abyss, and a hide crisscrossed with scars. “What are we to do with this?” demanded Ross.

The Inuit Saki, who had come out with them on the Felix and who had been watching the fishing operations with great avidity, gestured at the shark and spoke. “We don’t need the whole thing,” explained Minik. “Just the liver.”

This — sixty pounds’ worth — they chopped up and stored in two casks, nostrils flaring from the reek. The rest went into the water to be devoured by the shark’s kin. “This man had better exist,” growled the captain. Seeing him glowering, Saki nodded once, gravely.

Their guide directed them east along the sound, taking obvious enjoyment in his role as navigator, until the land was covered by the ice sheet, its mottled edge like an old man’s teeth. Soon they came to a little cove, where the glacier scooped inward to reveal a meager expanse of steel-gray gravel. “Shall I take the boat, Captain?” asked the first mate, Will Foster.

“No. I’ll go,” said Ross.

“There might be some climbing involved,” Foster said solicitously, stopping just short of a suggestion.

At seventy-two, Ross was easily the oldest man on board, and though he was hale yet, he knew much of his crew thought he’d be better off dozing by a fire. Sometimes, given the way his joints ached, he tended to agree with them (though the scurvy was no doubt also partly responsible for his pains). “I said I’ll go.”

Seeing the Captain’s determined expression, Foster just replied, “Aye aye, Captain,” and in minutes the oars were in the water, the surface choppy.

Foster wasn’t wrong about the climb: From the beach they faced a short treacherous climb up the face of the glacier, aided by ice axes and steel teeth on their boots, then a mile-long trek across its surface. Ross regretted the lack of exercise aboard this last year, with the climb leaving him gasping, wondering if he had indeed made a mistake. Of course he did not complain, nor did the others; to sail the north seas required a fortitude not much known among those in gentler climes.

But even these hard men balked at the mouth of the stinking hole where Saki led them. “That’s a bear’s den or I’m a Halifax whore,” swore Jenkinson, setting down the cask strapped to his back.

“This Indian’s playing us for fucking fools,” agreed Mackay. “He’s going to run off, any minute now.”

To be sure, the four-foot orifice in the ice was singularly unappealing, the path inside streaked with yellow, orange and pink stains, the air thick with the smell of rotting flesh. It could well be a bear’s den. Ross jerked his chin at their guide. “Him first.”

Saki spoke, Minik translating. “He says no more than three people at a time. Otherwise Anguta may hide from us. Also he says to be careful and treat Anguta with respect. Anguta is very old, older than his grandparents’ grandparents’ grandparents, and knows many powerful spells.”

“We need four at least,” Ross said. “And I don’t much care if this pagan likes it.” He turned to the surgeon, McCullough, who had come along to help if indeed they found a sick or injured man, and nodded at one of the casks of liver. “Can you handle one of those?” With Ross himself, Minik and Saki made four; along with lanterns and ice axes for each man, Ross and Minik had rifles over their shoulders, Ross and McCullough revolvers as well. One by one they ducked inside, backs hunched.

In moments the sounds and light from outside were cut off, leaving them alone with their breath steaming in the lamplight, the stench truly hellish. Like the bowels of Satan himself. Twice other tunnels joined this one; there could be a whole warren down here, and likely was.

He guessed they had traveled thirty yards — a long way under the ice — when the tunnel dropped three feet and opened into a cave. Saki and Minik had already moved to either side to allow Ross and McCullough passage; and so when he slid into the chamber, the momentum nearly caused him to careen into the figure seated there before stumbling to his knees, eyes wide and lantern thrust high.

At first he thought it was a statue, set on a waist-high ledge in the ice at the rear of the cave: a totem for these devil-worshiping savages, surrounded by a heaped miscellany of offerings. Lifting the lamp, he changed his mind: not a statue but a mummy, its eyes and cheeks sunken, flesh gray-black and wrinkled as a raisin, lips grimacing to expose black gums and carious teeth, a few long white hairs still streaming from chin and temples. It had been placed there naked and cross-legged, a stone knife in one withered hand and offerings piled all around it: carved boxes, urns, knives, hooks, desiccated furs, a trove of primitive treasure. Ross was a hard man, in truth — had undertaken six voyages in the harshest known conditions, witnessed dozens of deaths — but even so a sick fear sank into his belly, faced with this unholy idol.

McCullough slid into the cave behind him, nearly sending his captain again tumbling into this macabre relic. “This is a catacomb,” accused Ross, coming slowly and carefully to his feet. “There’s no one alive down here.” Probably they brought bodies here they did not want decomposing; obviously they would freeze and thus last for centuries.

Saki gestured at the cask McCullough had set on the stained ice floor, indicating they should open it. Ignoring the fresh wave of odor — the same odor that permeated the cave already, from juices that coated every surface like rust — Saki unsheathed a slate knife, speared a large chunk of the orange-white shark liver, and carefully extended it under the nose of the mummy.

The thing inhaled. It opened its mouth. Even Saki jerked backward, before recovering himself and holding it out again.

A claw hand shot up, seized the piece of liver and brought it lovingly to its withered lips, though its eyelids remained closed and Ross was convinced it was blind. A black tongue flecked with crimson crept from the lair of its mouth like the head of an eel to taste the meat. Slowly, hungrily, it began to feed.

In a hoarse voice, McCullough said half in question, “It’s been here a long time.”

“Since the earth and sea came apart,” Saki replied, through Minik. “For as long as people have been here. Anguta sleeps and wakes and sleeps again.”

A rasping croak came from the mummy-shaman, bits of soft fatty flesh dropping down its chin. Ross shrank from the sound, hands clenched around his rifle. “Can you understand what it’s saying?” he whispered to Minik.

“Yes,” whispered the terrified translator. “He knew we were coming. He’s been waiting for us.”

“Because of the sailor.”

“The sailor is in the cave over there.” Anguta pointed a single stick finger. “But he’s not who you’re looking for. The men of the Erebus are dead.”

Ross jumped again, as though goosed, hearing distinctly the name Erebus pass those wrinkled black lips, now thick with grease. “How can he possibly know that?”

The shaman began making a repeated coughing sound, and flinching from the rotting-fish scent of its breath (which unlike their own made no plume in the freezing air), Ross realized Anguta was laughing. “I tasted it in this shark’s liver,” said the shaman.

“I don’t believe you,” rasped Ross. “The sailor they brought here told you that.”

“How long?” repeated McCullough.

In reply Anguta tossed down the piece of liver, then reached into a nearby wooden box, a box filled with dull silver coins. He held out a handful and let them drop to the floor of the cave, one rolling until it fell still at Ross’ feet. He picked it up, examined the runes and the crudely stamped visage of a Norse king. McCullough extended his hand and Ross numbly dropped it into his palm.

Anguta said, “The lives of ordinary men melt like snowflakes. I sleep and wake and sleep and wake again. I thought perhaps soon I would sleep and wake no more, but you stir new life in me. Stay, serve me! I will teach you life everlasting.”

Ross took a step back, caring no more about whatever unfortunate sailor lay here, whether alive or dead. “I’m old,” he said finally. “But I’m a God-fearing man and no fool. Even if I believed you, what kind of life could you offer — sitting in a cave, gnawing on filth? What knowledge do you have, besides how to cling a little longer? Better to die and be resurrected.”

Anguta laughed again, a knowing croak. “Go die then, so proud. Others know the gift I offer.” His blind gaze turned.

The surgeon, McCullough, was mesmerized. He crept forward, picked up the gobbet of liver, dripping vile poison. Eyes fixed on his future, he beganto eat.

Joel Tagert is a fiction writer and artist and the author of A Bonfire in the Belly of the Beast and INFERENCE. He is also currently the resident manager and chef for Rocky Mountain Ecodharma Retreat Center near Ward, CO. See more on his Website and on Instagram.

Graham Franciose grew up in the forests of Massachusetts. His work reaches back to those times of exploration and imagination, where anything was possible. His whimsical, sometimes emotional, illustrations show a sliver of a story, a moment between the action, leaving the exact circumstances and narrative up to the viewer. There is sense of familiarity and honesty within his characters and scenes, as well as a sense of mystery and wonder. Graham received his BFA in Illustration from the Hartford Art School in ’05. He originally wanted to pursue Children’s Book Illustration as a career, but his personal work has taken center stage over the last few years. He currently lives and works as a professional artist and illustrator in Austin, TX. See more of his work on his Website and follow him on Instagram.

Check out Joel’s last Birdy install, The End of Stasis, and Graham’s, No Kings, in case you missed it, and Ali’s last Birdy piece, Shroom, or head to our Explore section to see more work by these talented creatives.

Pingback: The Assassination of Snuffkin McGillis by Joel Tagert | Art by Hari Ren - BIRDY MAGAZINE