Published Issue 123, March 2024

One of the era’s most prolific conceptual artists and composers Mark Mothersbaugh has been making postcard art every day for the past 50 plus years. And this is on top of composing and scoring over 150 films, television shows, video games and hundreds of commercials and interactive pieces through his multimedia studio, Mutato Muzika. All the while making music and performing with pioneering band, DEVO.

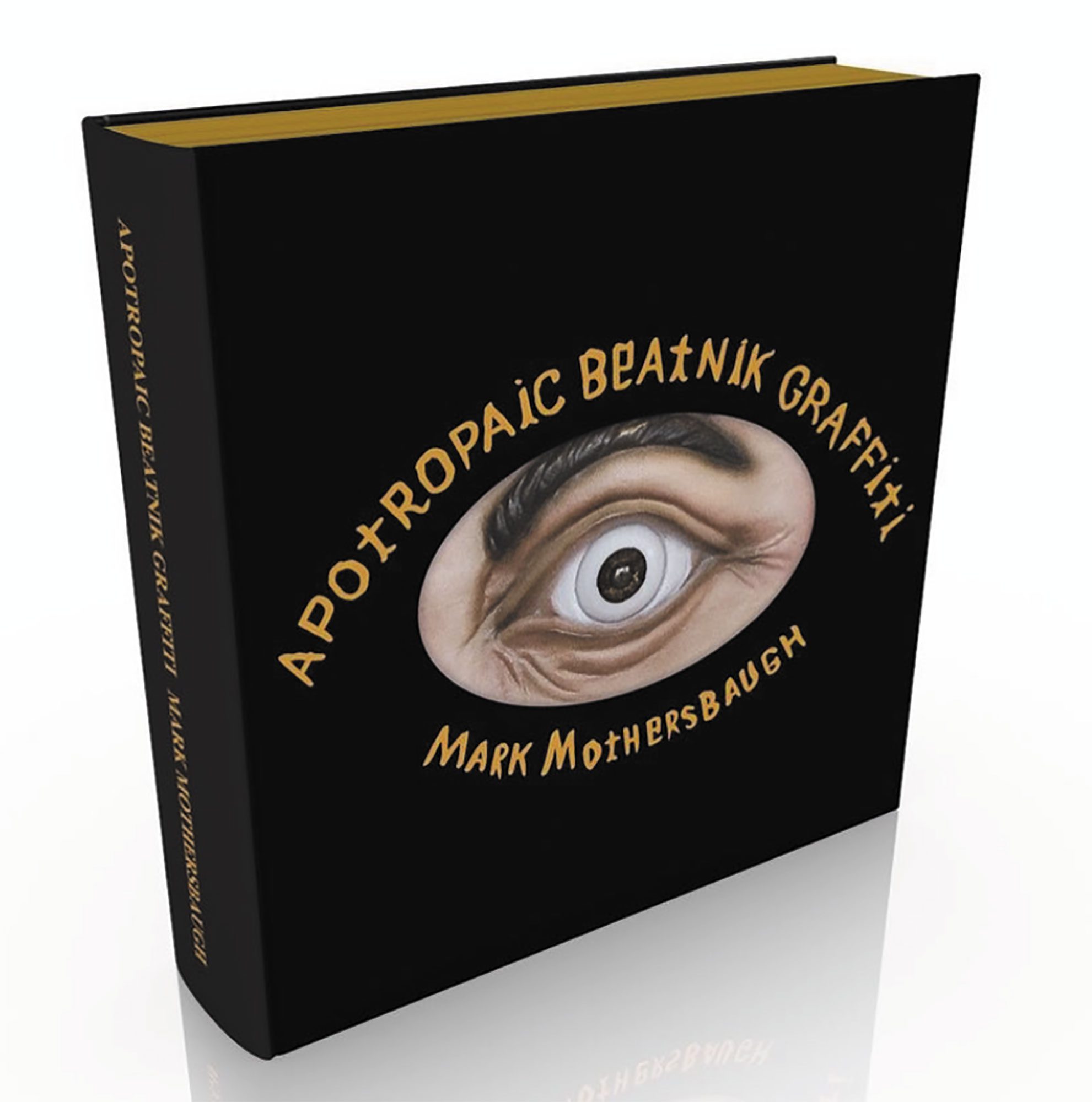

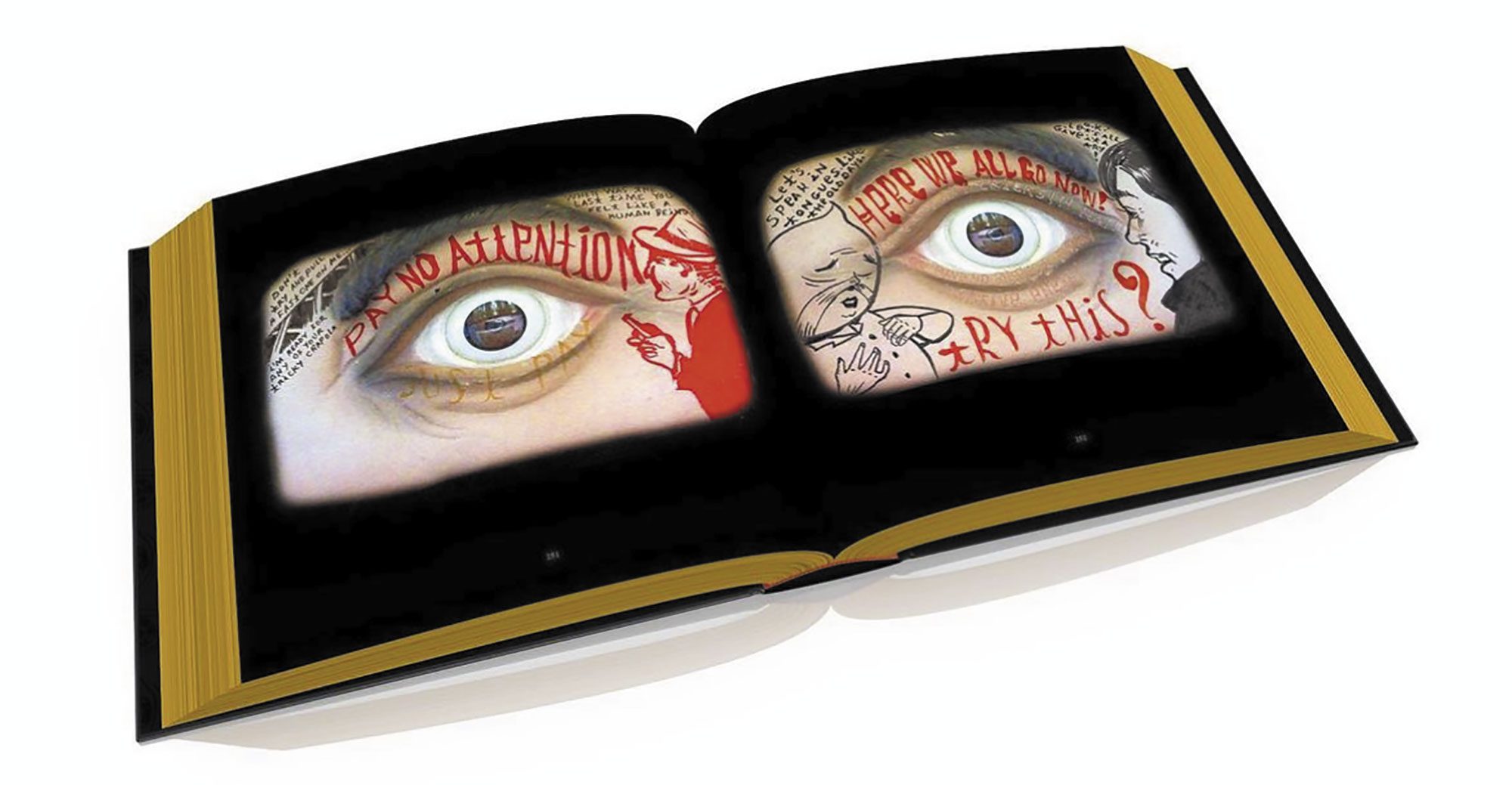

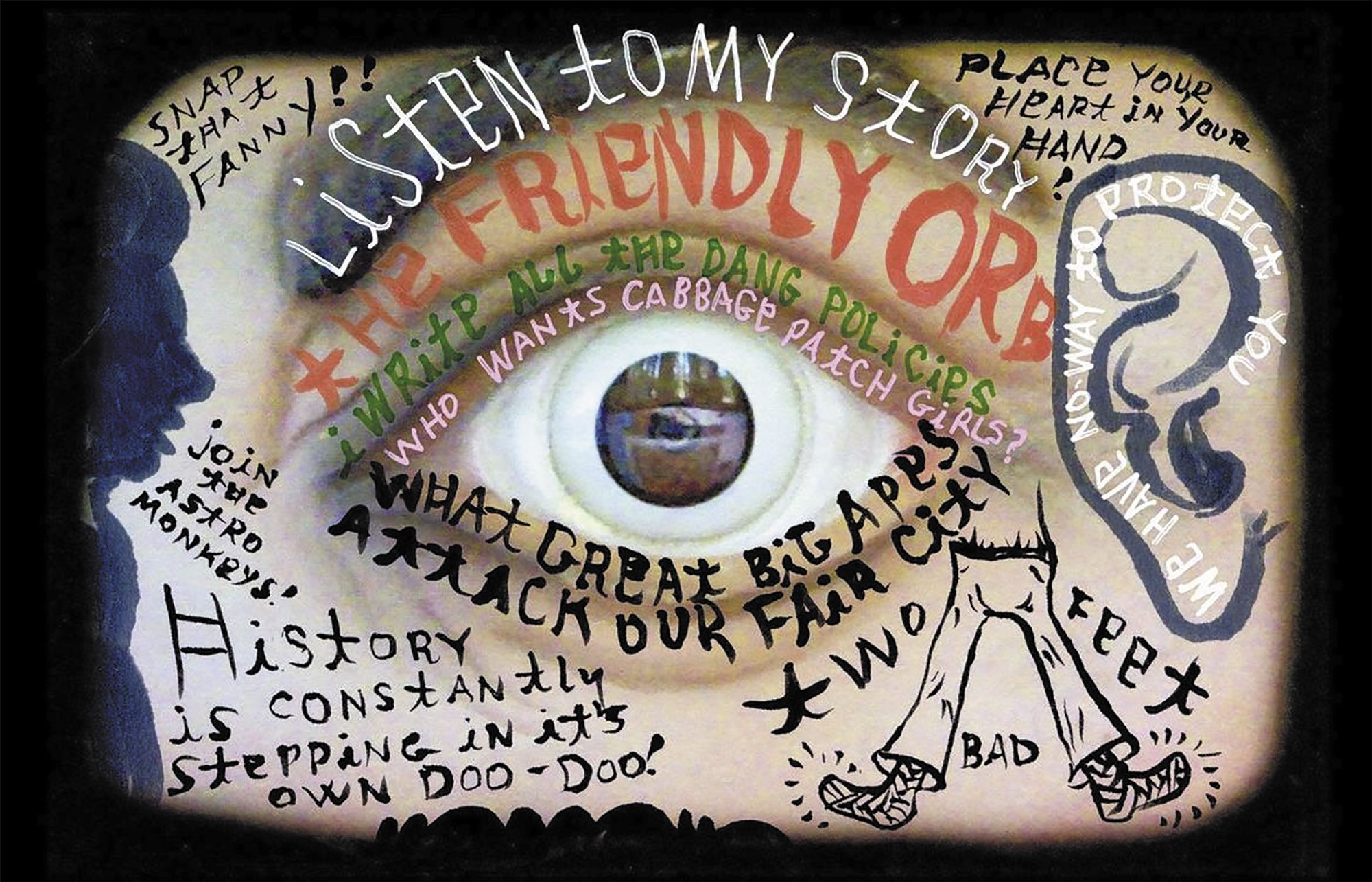

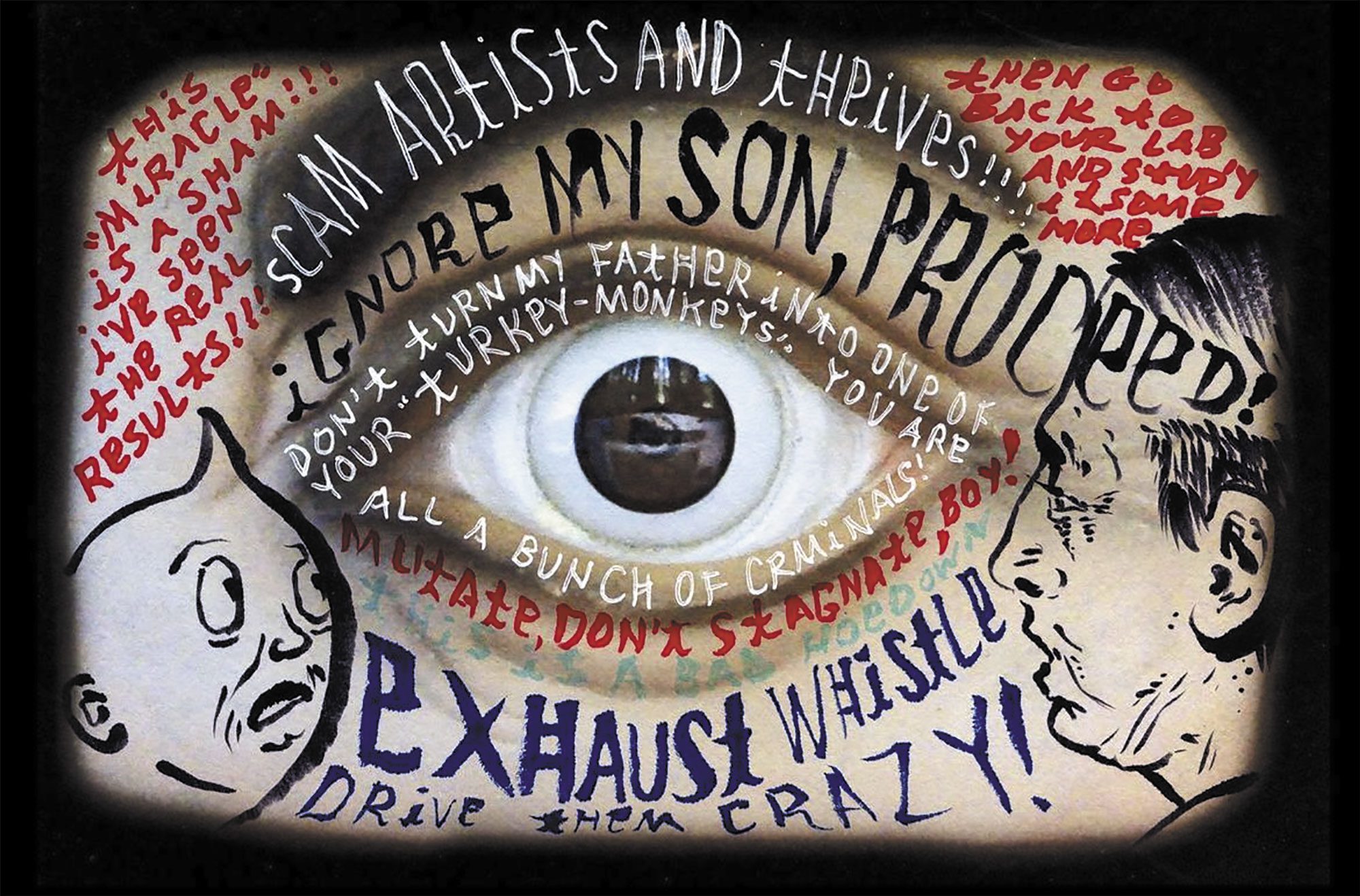

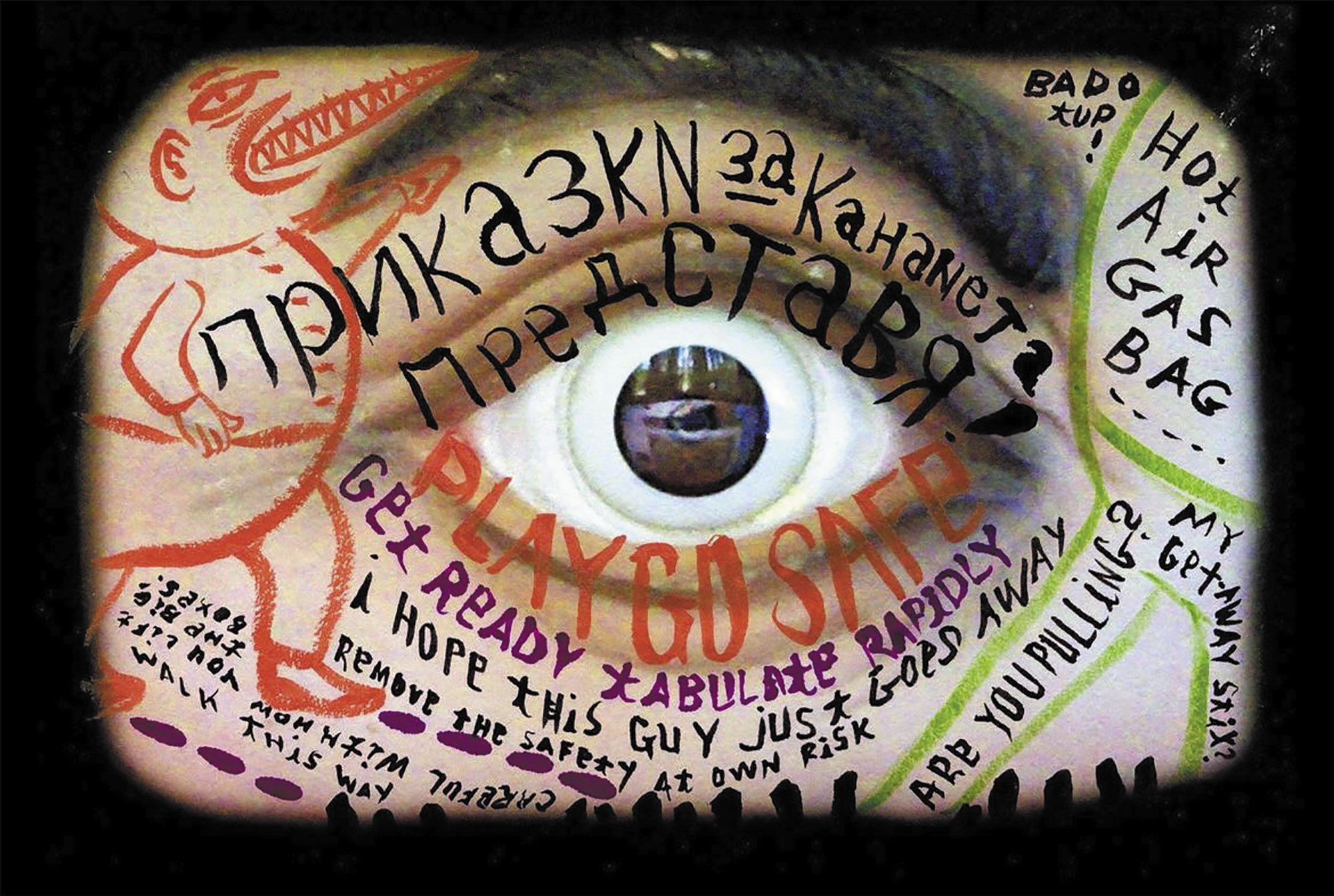

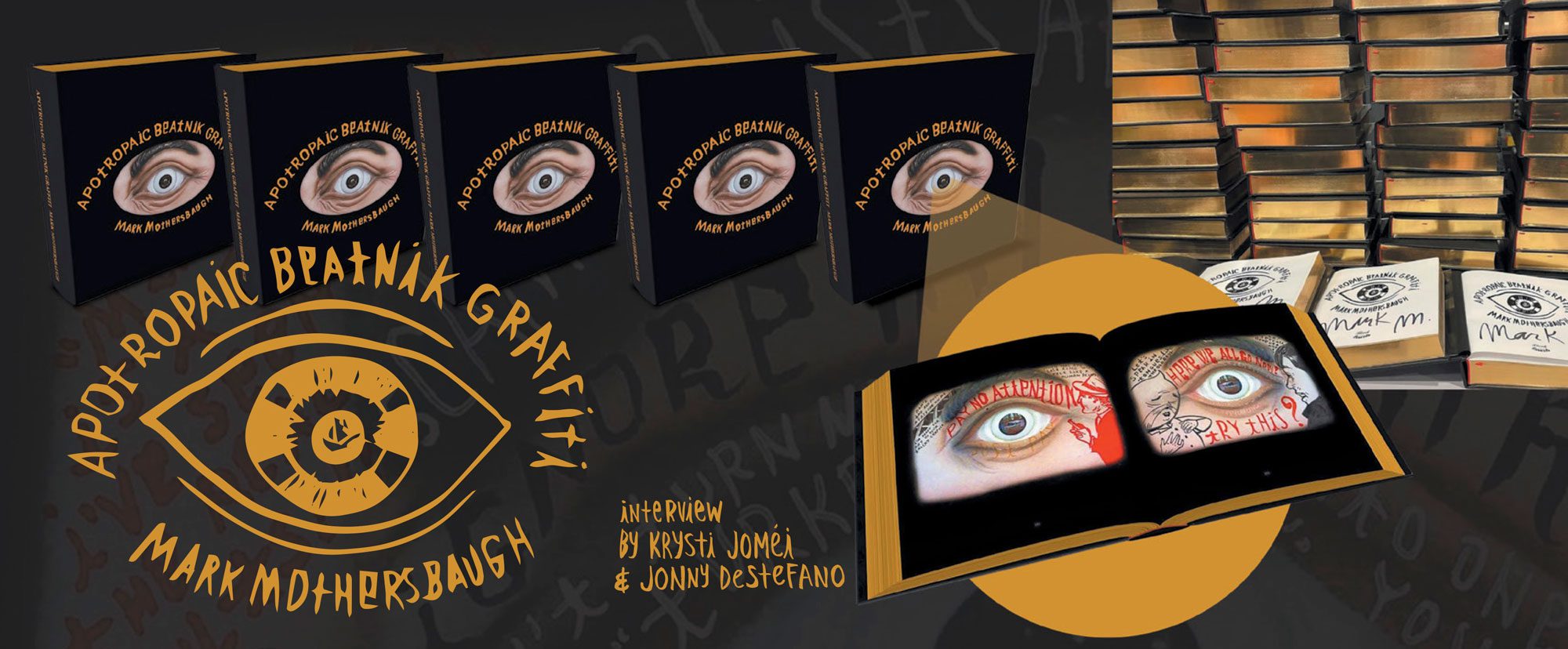

After he thought he was told that his “potscards aren’t art,” Mark set out to create books that explained his favorite medium and practice with one out now: Apotropaic Beatnik Graffiti. Released by Blank Industries, the neo-dada Beatnik stream of consciousness poetry and graffiti book represents one human’s shamanistic observations of life in a wiggly world, and it’s all centered on eyes.

We had the opportunity to catch up with Mark and his artist-in-chief, Siena Goldman aka S. Putnik about the book.

Krysti Joméi: I ordered the first edition as a present for Jonny.

Mark Mothersbaugh: Sorry, it didn’t come for Christmas. You should just say you want a refund now.

Krysti: Yes! I want a refund from the artist. (laughs)

Mark: I’m delighted that we’re doing this.

Jonny DeStefano: Thank you Mark. So let’s talk about APO-TRO-PAIC Beatnik Graffiti.

Krysti: We’ve been practicing that — A LOT.

Mark: So you know I draw postcards every day. You’ve been a supporter of that by publishing them in your magazine, which delights me to no end. The two things I enjoy most are getting up in the middle of the night and making a card and showing up at the studio before everybody else is here and writing a piece of music that’s not even going anywhere. It’s just gonna be in my car and that’s it.

So five or six years ago, I said something like, “I do art every day” to somebody, and they said to me — or at least I thought they did because I have tinnitus issues because of Devo — “Those postcards aren’t art.” And it was somebody that had watched me do them every day for a long time. And I was like, wow, that’s interesting that somebody that knows me really well had that take on it and it made me think, Well, I want to do a book about the cards to explain them. That was how it started. I wanted to take all these cards and present them like a diary — one man’s observation of planet Earth.

I used to give away these cards and they’re different every time. Sometimes they’re on top of an actual old postcard or sometimes they’re on paper that I pre-prepared with images, collages or things. And they always were a way to store pieces of information that I observed or overheard or thought about or had a nightmare about or was bored out of my mind and just started drawing something. And I was kind of surprised. I didn’t even know what I was doing when I started and it came out to be something by the end. And I had started putting them in red binders. You’ve seen pictures I think?

Krysti: Yeah! At Myopia [Museum of Contemporary Art Denver, 2014-2015]. Your postcard room.

Mark: Before I did the Myopia show, it had never occurred to me to take those books and open them up so public people could walk in. The idea was shocking to me and I resisted it for a while, but Adam [Lerner] [former Director of MCA Denver] was insistent on it. He is a very amazing human and he curated the show. But when I saw them laid out like that it made me think about them in a different way. It even changed my art a little bit because it was so private before that. I said and drew things that I wouldn’t want anybody to see. I was in shock when we were setting up the show the first day. I started pulling [binders] out, thinking, Nobody should see that. They would definitely get the wrong idea.

And though this should be at the end of the story, when I told that person who said to me, “Those postcards are not art,” that’s why I was doing these books [Mark’s bigger book in progress and Apotropaic Beatnik Graffiti], they went, “I never said that!” And I thought, Oh, shit, I probably should have asked them to repeat that instead of just being in shock when I thought they said something they didn’t say. But it did make me start wanting to put together this bigger book. And I thought, I’m going to go through all these [red binders] and start pulling images out of them. And at first I was going to do it properly archived by time. Then I realized I’m at odds with our part of the universe.

There’s a part of me that’s really pissed off that we’re in a part of the universe where time just flows one direction. You know, it’s not that way everywhere. Somewhere in the universe there’s a bow tie right here, a knot, like a birthday bow and you could go phew — 1976 — vroom back again — oh, 2007, oh — here we are again — 1842 — and you could go off on these loops and come back. For a long time, I’ve always wished I was in that part of the universe instead.

Well I told a publisher who had been calling me what I was doing and they said, “You don’t make any money on coffee table books.” They wanted to do black and white pages so it was cheap to print. And I go, “I’m not trying to make money on it, I just wanna have this idea out there.” I just wanna explain why I have this storage container at a warehouse that’s 20 feet long and 8 feet high. And the walls have 700 red binders that each have 100 pieces of art that I’ve done in them. Because I don’t know what’s gonna happen to them if I like, walk home off a stage next year with Devo and impale myself on something and I’m laughing about it saying, “Oh, fuck, I died with a yellow plastic Devo suit on!” I’m going to think, I wonder what’s going to happen to those cards if nobody’s really looked at them or has any idea that there’s a reason for them. Maybe they’ll just all end up in a dumpster.

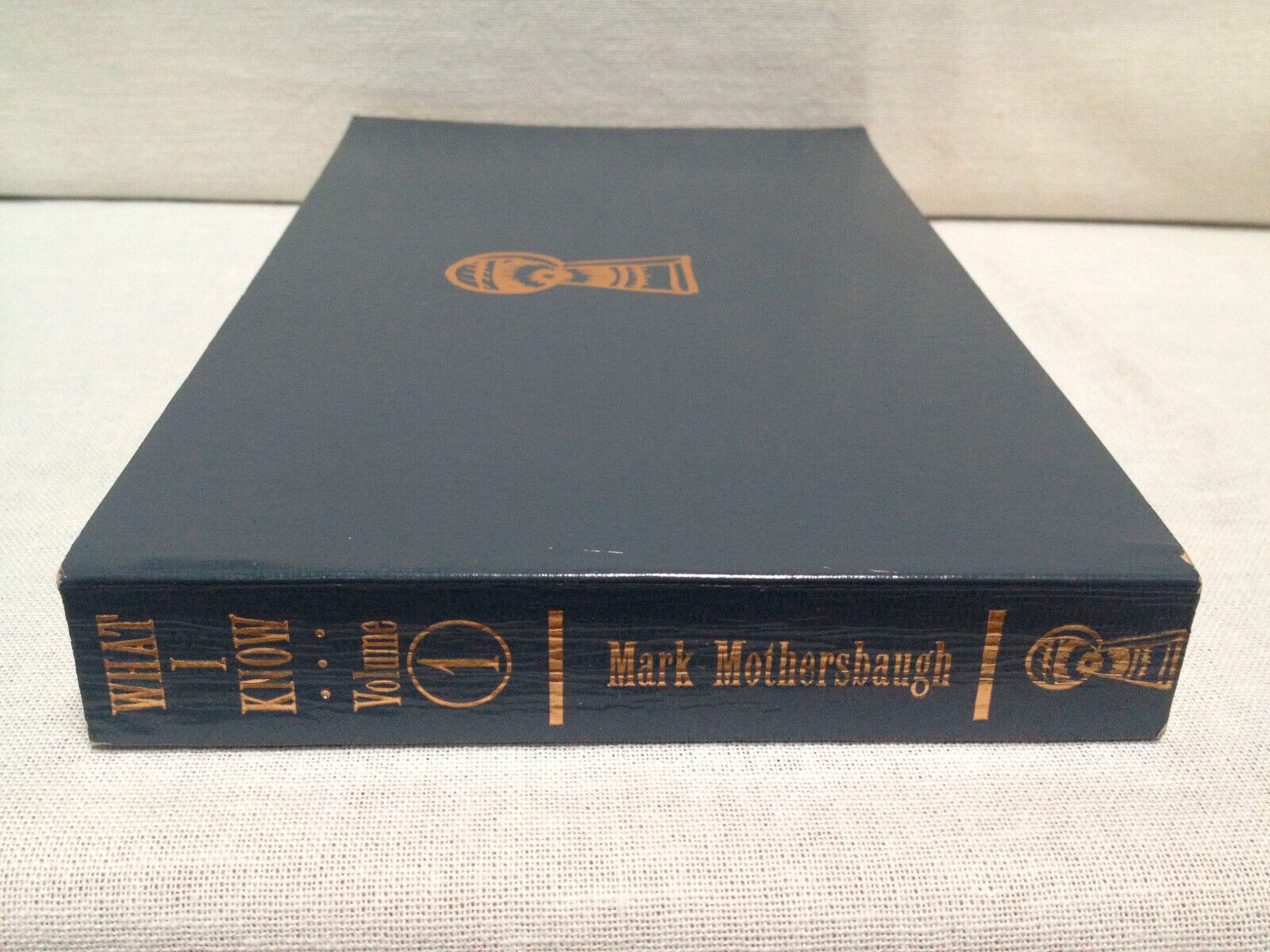

So I thought, I’ll just do Blurb books. It doesn’t have to have pages with black and white words on it. It can be all imagery and all pre-existing statements, phrases, poetry, observations, illustrations, collages, collected imagery, all this stuff that I’ve been doing for myself. But there are limitations to what you can do with Blurb. So I thought it’s going to be four editions, this 1,600 page, 11-inch by 17-inch size book, and they’re going to be expensive.

So I’m putting this book together and it just coincided with this guy I knew, John [Bakasetas], [of Blank Industries] who called me up one day and said, “Hey, I’m doing my first book with a photographer from LA. She shot the LA punk rock scene between the late 70s and early 80s.”

Siena Goldman aka S. Putnik: Melanie Nissen.

Mark: He says, “I was wondering if you have recordings of Devo at Starwood. She took a lot of pictures at the Starwood and I have three other bands like Go-Go’s, Germs, and the Dils. And she said, ‘I’d like it if each of you did a song to put on an EP and in the back of the book.’” And I was like, “Oh yeah, that sounds interesting.”

So John happened to be bringing over the book one day and he was totally jazzed. And Putnik and me loved it. And I go, “You’re gonna laugh, but I’m making a book right now,” and we showed him. We had about a third of this big book in progress, like 600 pages. And he said, “Let me put out your book.” I’m like, “Don’t get involved, this one’s a weirdo book. I’m making them one at a time because not many people are gonna understand it or be interested.” But he says, “I want to do it.” And I go, “Well, I’m not going to hold you to it. But I will keep you up to date with what we’re doing.” While I was working on the book, after he left, I thought, Wow, what if he really got it printed instead of Blurb?

I collect books, catalogs, comics, a lot of things from older times. And I remember seeing these catalogs that came out in the 20s and 30s that had over 1,000 pages in them. They were beautiful books and they had this spine that was separate from the back part of the book, so I said to John, “Hey, if you’re really serious about this, would you do a little research and find out if there are printers that can still do a spine like that?” And I showed him what I was talking about. And he got on the project really fast and came back and said, “Yes, I found people that can print and bind in that fashion. And you could have a 1,600-page book if you really wanted to.”

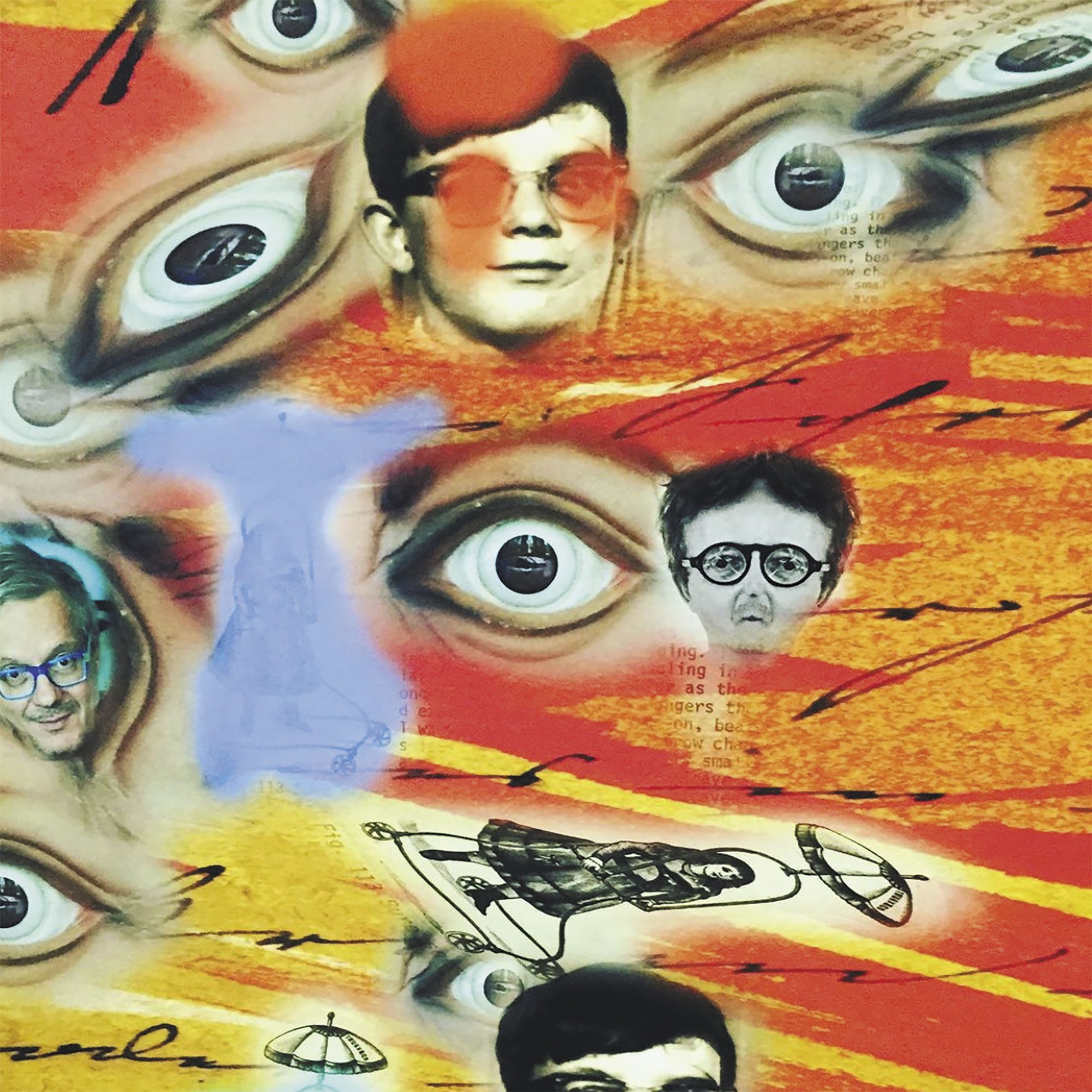

With that, we’re working towards that book. And while we were putting it together, I found that there were like, seven or eight volumes [of red binders] that each had 100 cards that looked really similar, that were all eyes — it was after Myopia that I started doing a lot of eyes. And I remember there was this period in time about 14 years ago where I had taken this plaster [eye] medallion, a wall hanging that I’d found at a botánica store in downtown LA, like probably ’77 to ’79. I used to be fascinated with those kind of shops and I loved going in and there’d be incense, or candles that you burned if you had like a lazy husband, or if you had a cheating wife, or if you wanted to make more money, or if your car wasn’t running properly. You could buy these things that would channel energy towards these different places in your life to help you solve problems. And there were these eyes that protected you from the evil eye, from evil doers and malevolence. And you would take an eye and hang it maybe on your front door or above your bed. And you would have it as an apotropaic element. And I loved all that stuff, but I’d found these [medallion] eyes that were really detailed.

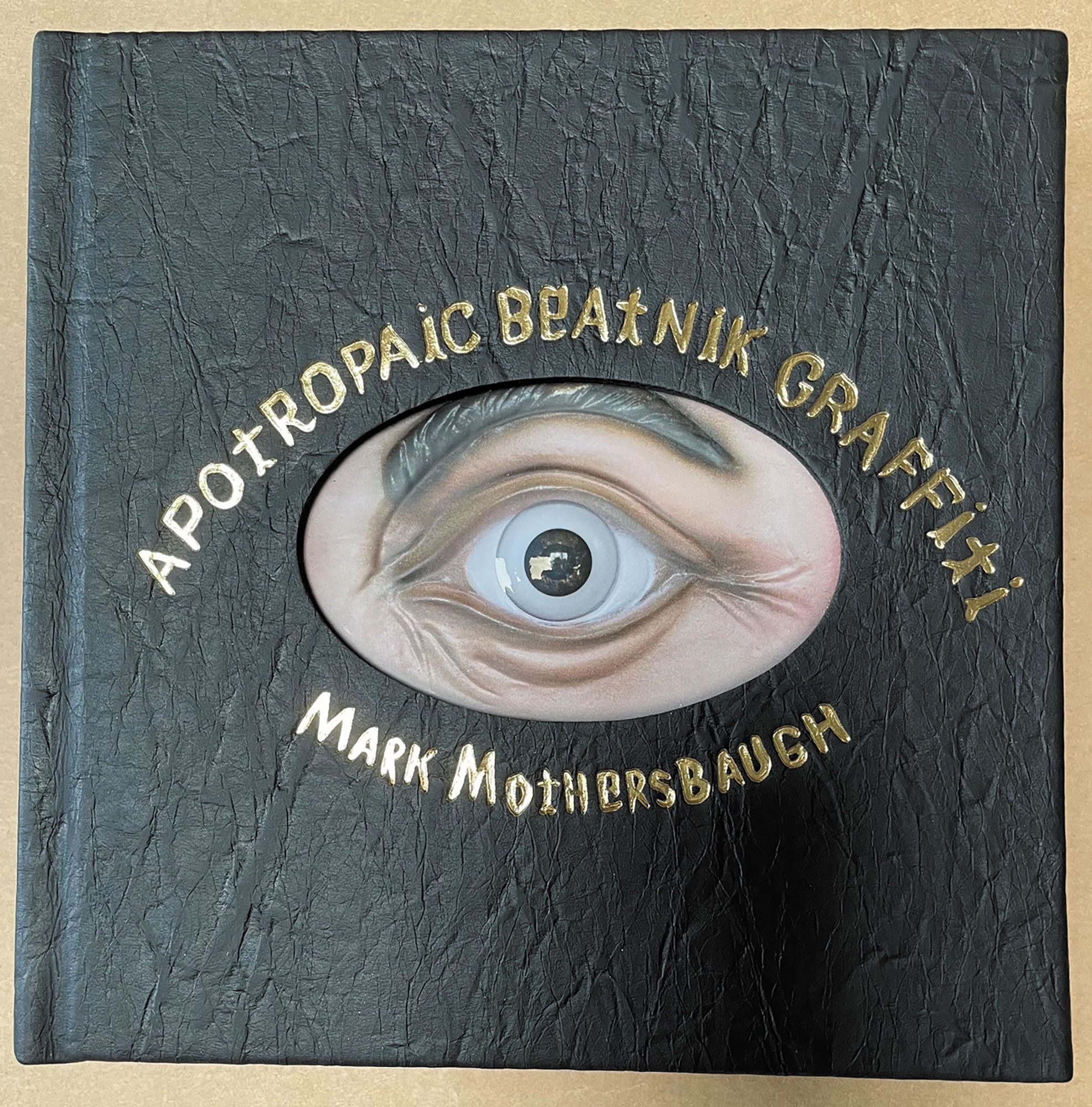

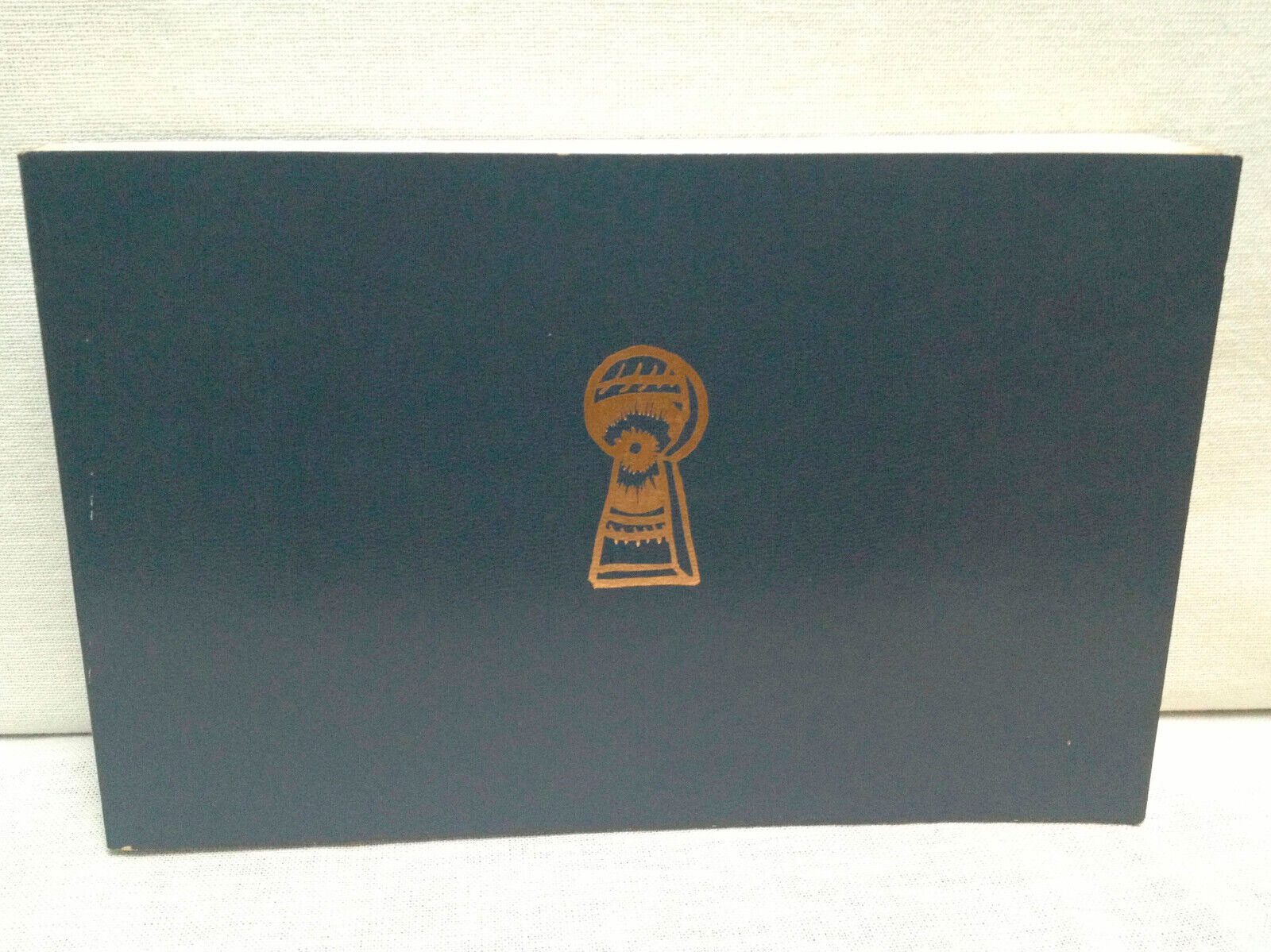

Like this is what the plaster eye looks like (shows the front cover of Apotropaic Beatnik Graffiti). It’s a lure to get somebody to buy the book — it’s three-dimensional and shiny and fun.

S. Putnik: And it’s staring right at me.

Mark: It’s the basis. And so I wrote things and I drew things around them, like, um …

Jonny: Stream of consciousness.

Mark: Yeah. So there’s text and it’s all kind of abstract. During the time period I was doing these two books, I was thinking about Beatniks because I remember when I first started working with Jerry Casale, writing music with him, his lyrics back then, to me, sounded like Beatnik poetry. And when I was a kid, I just missed the Beatnik thing. I was in high school in the late 60s, and I remember driving up to a house that was a Beatnik pad in downtown Akron, close to Akron U. And you’d hear music inside, it might have been bongos and a guitar. And you knew they had espresso in there. Maybe they had marijuana. But I didn’t even think about that stuff then. I was like too intimidated when I was in high school to go into one of those places.

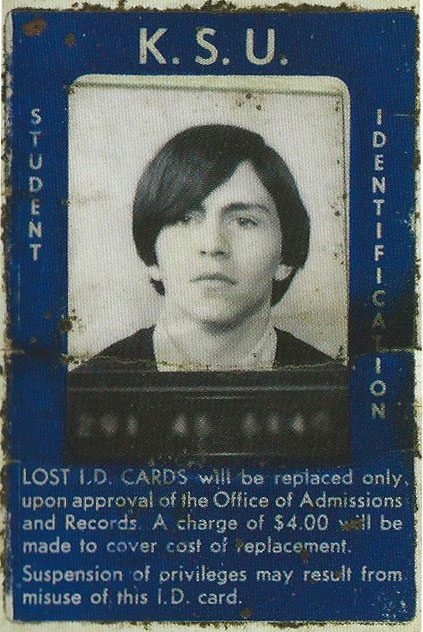

And then when I went to Kent State, there was one right across the street from the main entrance to the campus. And people would go in and sit around, drink coffee, talk about books, politics, all the things that a good Beatnik does. And I liked them because to me, Beatniks were the first art movement, book movement, intellectual movement post atomic bomb in the U.S. And they were like, “We fucked up. We went too far.” They were pre-Devo. I think a lot of our concerns about humans were very similar to Beatniks and the Beat world.

And so I became interested in this similarity between Beatniks and punk rock about the same time I was doing these books. And there were people — like Jerry would argue with me. He’d say, “No, the difference between Beatniks and punk is punk is stupid for the most part.” I go, “It’s not all stupid though. You have to admit that.” And punk does have things in common with Beatniks as far as rejecting society and things like that. It made me set out to look for the similarities and in the process, I realized this guy that I’d known since 1977 had done a San Francisco fanzine called Search & Destroy, which I think was the best punk rock review magazine. His name is V. Vale. I just happened to be talking to him a couple years ago about Beatniks and punk. And he goes, “I’ll tell you a connection. I don’t know if you know this, but two people gave me money to start Search & Destroy — Allen Ginsburg and Lawrence Ferlinghetti.” They each gave him a hundred bucks and that’s how he started the magazine.

So I started looking at these pages, the ones with all the eyes, and I thought of them as little like Beatnik. And they’re kind of graffiti too, because I blew the eyes up poster size for my first Beyond the Streets show (2018) and then I painted on top of the paper. I did like 20 of them. I really got into this imagery and I thought, It’s taking a while to get this big book done. I could put this eye book together really fast. Because if I took five of those red binders that are these eyes, that’d be 500 images with stories on them. And that could be an interesting book.

And so we kind of mocked it up and liked it so much. I said, “John, we’re going off track for a minute. But here’s another book.” And then he could afterwards like chicken-out of the bigger one that’s going to be expensive to print up even in small numbers. So we printed, like 1,500 copies of [Apotropaic Beatnik Graffiti].

S. Putnik: We got V. Vale to write for it.

Mark: V. Vale wrote an introduction, his is so sweet.

S. Putnik: It’s a “how-to” read this book.

Mark: I asked a couple other people to write forwards too and one of them was Ian Svenonius, who wrote the first book I read after I got out of the hospital. I volunteered to be a guinea pig for COVID back before they had any way to treat it. And so I went into intensive care and had a terrible experience. But when I came out, I read Psychic Soviet by Ian Svenonius.

S. Putnik: I gave it to you (laughing)

Mark: (laughs) Putnik gave it to me. And because I liked the book so much, I asked him to write something. And his introduction is really nice and totally different than Vale’s. And then I asked a third person, Bob Lewis, who was around in the very early days of Devo. And he helped come up with the term Devo.

And de-evolution existed of course, because ever since Darwin came up with evolution, there were religious people that freaked out and then made jokes about de-evolution. And there’s always been this thing between science and faith. I think they both need to work together a little more, because both elements have definite use in the human experience. But to this day, they’re afraid of each other. It’s kind of interesting.

Jonny: I wanted to say when I was a a teenager I ordered What I Know (1987). But I remember [the book cover] was like a keyhole with an eyeball through it. And by just seeing [Apotropaic Beatnik Graffiti] opened up. It’s two eyes looking at the reader. Just like What I Know, I can’t help but think it’s you, observing the world, recording, looking at us.

Mark: You know, eyes have always been an issue with me. It’s a toss-up, whether it was beneficial or mostly worked against me. I couldn’t see further than 6 inches of the big E on an eye chart. I got all the way through first and second grade, without anybody realizing that. And everybody just thought something was wrong with me. There was, because I couldn’t see anything. People take their vision for granted.

About a month before second grade was over I walked out of an optometrist’s office and he had given me glasses that made everything in focus. I mean it was shocking. Between walking out of this place and my dad driving to my parents’ house, in that 10 minutes I saw things I’d never seen in my whole life. I saw the roof of a house. I saw smoke coming out of a chimney. I saw clouds. I saw the sun. I saw birds flying. I’d never seen that. I only knew the part of a tree that was down where I was and I’d run into it when I was playing in the yard. But I never saw what a tree looked like with leaves. It was mind-blowing. I was so happy and so amazed that I just started drawing things I had seen for the first time.

And I remember this teacher who didn’t know what to do with me, she was at wit’s ends because she would say, “Alright Mark, add up the numbers on the blackboard.” And I go, “What’s a blackboard?” And all the kids would laugh. Then she go, “Alright smart guy, go stand in the corner.” How do they know the right answer to that question? I was just totally made to be confused and I had no idea how kids knew what to say.

The next day I’m back in school and I’m drawing a tree, because I had just seen trees, and [that teacher] was standing behind me, Mrs. Savory. She said, “Mark, you draw trees better than me.” And it was the first nice thing, positive thing any school teacher had ever said to me. It was the first time somebody wasn’t saying, sit up or shut up or write this, add this up or read that or do this, and they’d be mad. I know about wearing a dunce cap and getting spanked in front of the other kids as an example of how not to behave.

So I got these glasses, it was so awesome. She said this and I went home that night and dreamt I was gonna be an artist. I knew when I was in second grade that’s what I was gonna be when I grew up.

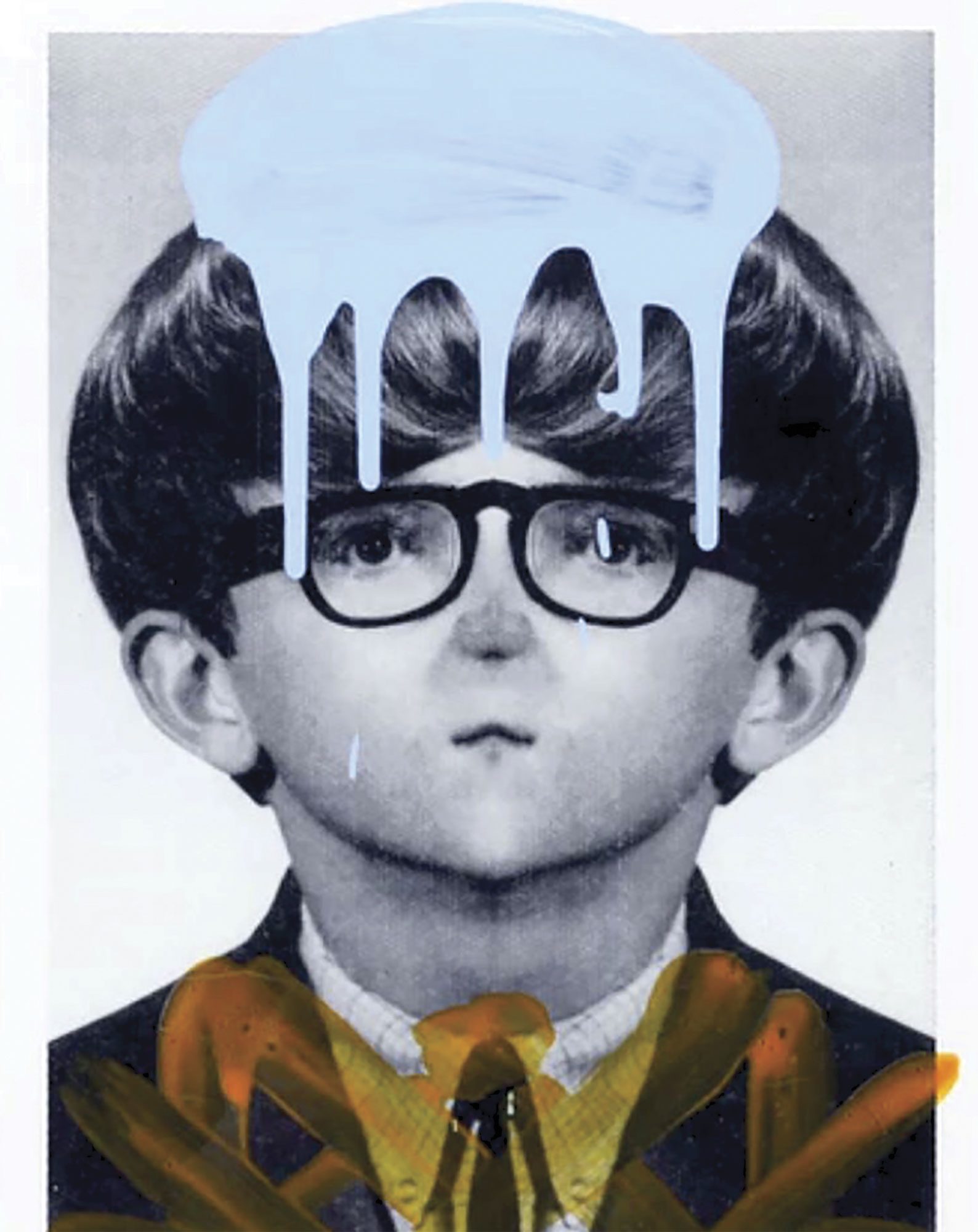

But the trade-off was that back in the 1950s, what you got for a pair of glasses to cure incredible myopia was basically two Coca-Cola bottoms and you looked like you had some space age goggles on. And I was like one of the littlest kids in the whole class, and I remember this girl in second grade said to me, “Why is your head shaped like a light bulb?” And I went, “What?!” and ran to the bathroom and looked in the mirror and I was like, Oh my God! My head IS shaped like a light bulb! Because I had a giant head and a tiny body. I just always felt like a space alien after that, but I got these glasses and adding that to having this big egg head, it was just like having a kick-me-sign attached to you.

So I fought with teachers and all of the other students my whole kindergarten through 12th grade. That was just my lot in life. And it wasn’t until I got to college that I became invisible. There was like 10,000 people at Kent State and I just blended in. I was just an anonymous person and that was so great. And I got to study art there. It was a total fluke. And that was a very happy time of my life.

But eyes have always been important to me because of the early days of my life. And it was kind of weird, when we were putting together Apotropaic Beatnik Graffiti, I remember thinking, I wonder if I put a hex on myself when I did all these eyes? Because when I got COVID, they didn’t know what else to do, they didn’t have medicine as it was the very early days, so as they were putting me on a ventilator— [He was hit in the eye causing him to lose vision in that eye].

But I came to the conclusion that no, maybe things would have been worse if I wouldn’t have done this book. Because I think even while I was in intensive care, these red books that were on shelves back in my warehouse were like watching out for me. They kept me from getting any worse.

So when we started putting this book together, I thought, These pages could be useful to people too. Somebody could say, “I don’t like the way somebody’s energy is going towards me,” and take a page and pull it out of the book and tuck it inside their shirt. Or put it in their wallet and carry it around with them.

Krysti: You were mentioning how because it’s non-linear, it’s meant to just be opened it up randomly. The first thing that came to mind was that it’s kind of like a Bible in a sense, or one of those poetry or even self-help books that you’re meant to just open and find these nuggets of wisdom. And you we were saying it’s meant to be interacted with, to have pages even taken out. I love that concept. It’s not just a book, it’s a tangible—

S. Putnik: Functional.

Krysti: Yeah! And it ties back to your love of tangible art, like your postcards.

Mark: You know, maybe I can get you guys to help me talk to a couple of the bigger hotel chains about letting us replace the Gideon Bible with Apotropaic Beatnik Graffiti. (laughs)

Krysti: (laughs) It’s like a tool you can use. And I love that because we make Birdy for that reason.

Mark: Quite honestly, I imagine there’s probably 1,500 people that’ll like this book. So I’m hoping they’re the ones that buy it. (laughing).

S. Putnik: My dad will.

Jonny: We love it.

Mark: And I like people that like to experiment in this medium, because books are at a weird time right now where they’re both endangered, and open for reinterpretation on what a book is. I hope people like this.

Krysti: I mean, I might be the biggest eye nerd other than you, Mark. I had a pretty big obsession to the point where all the parents that knew me and who got magazines when I was little would save eye pictures for my eye wall.

Mark: Oh you’re kidding! An eye wall. I love that.

Krysti: So EYE am the fan of this book.

Mark: Well, EYE, EYE, EYE. (Holds up the book cover over his eye). Eyes are a pretty primal element and lucky for us, whoever is responsible, nature, science or religion, or God, whoever did it, gave us two eyes so that you could kind of fuck up a little bit and go, “Oh! I just got an arrow in my eye. Oh, the other one works fine.”

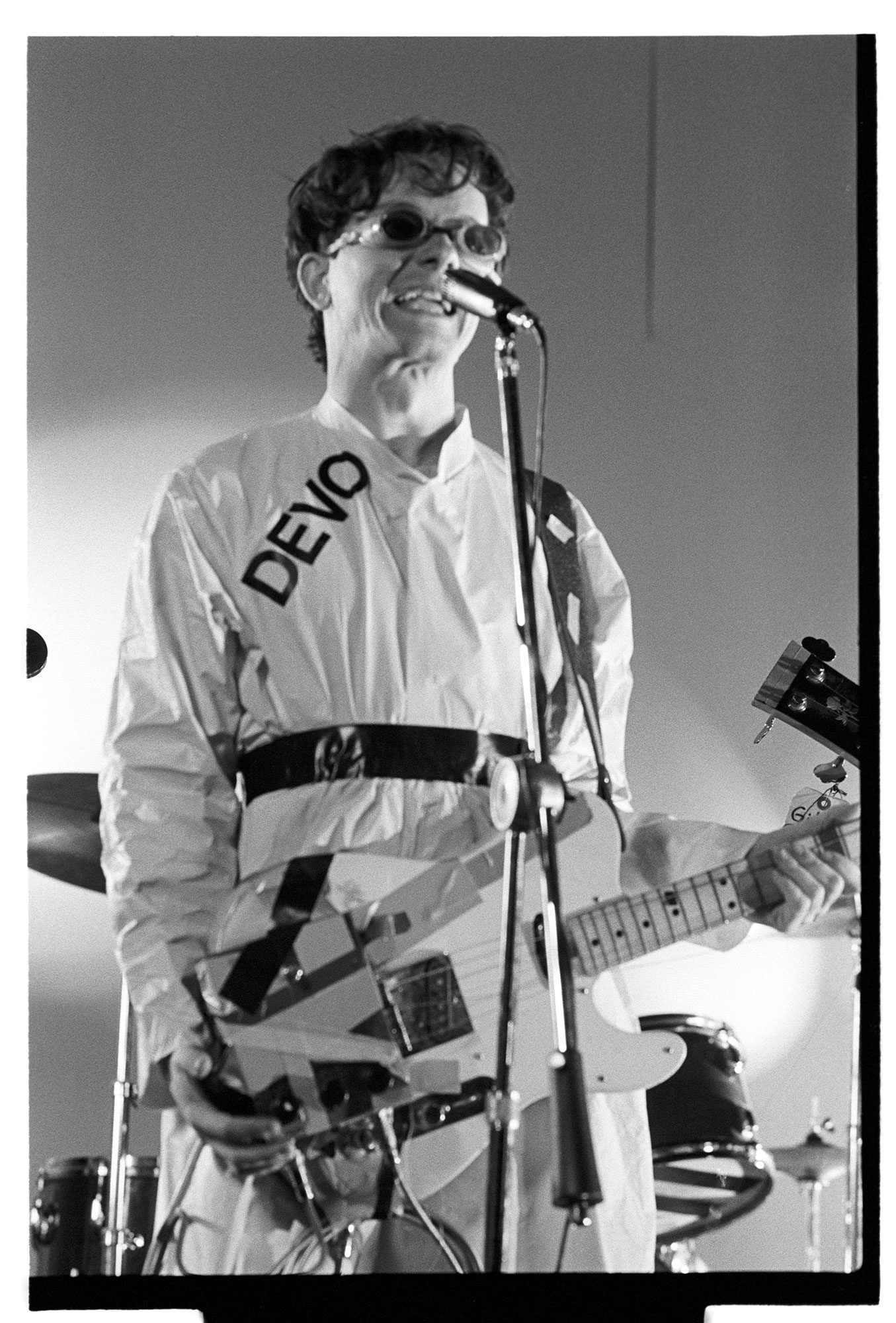

Jonny: I feel like you’ve made your eyes a superpower. I remember the “Satisfaction” video and you were wearing those goggles. To me, it was the coolest thing.

S. Putnik: It’s actually interesting because eyes have always been a big deal to Mark because of his childhood, because of his eyesight. He’s talked about when he would take his glasses off the world would look totally different and blurry and then he would put his glasses back on and the world would look like a fish eye lens. So he’s always had these weird morphed kinds viewpoints throughout life. And then especially me going through all of his artwork from when he was my age to now and he’s drawing all these characters with eyes or like one of the eyes exploding or something is happening with one eye. I think that he kind of predicted his fate during COVID. I pointed that out to you.

Mark: Damn it. No one to blame but myself. Hey! That could be the next album title. First dibs. Or that might just be a song?

Jonny: Love it. Also, to speak to the graffiti aspect of your book — I feel like Adam Lerner and people have acknowledged how you are an originator through posting your vomit stickers and potatoes in the early days of Kent State. I feel like Apotropaic Beatnik Graffiti is interconnected in that you’re speaking to your own place in history. And I like that you’ve tied Beatniks into it because I feel like Beatniks are rebels, and there’s an apotropaic element to them where they were rebelling against oppression, they were protective and they inspired all the artists, like Warhol and all the way up until now. And you were a big part of all that — artistically, musically. So I like how the title speaks to who you are.

Mark: You know, Devo — although we were calling humans the one species out of touch with nature and the one that was damaging the rest of the planet — we also had an optimistic side. We didn’t think it was going to turn out the way it’s been turning out in the last 10 years. We thought people were going to be able to go, “Oh, wait a minute. Let’s turn this plane back. So it’s flying level again.” It’s kind of crazy how close you can get to really stupid things happening on this planet.

S. Putnik: Devo was right.

Mark: Unfortunately. We weren’t supposed to be. But I think this book just follows in that. Although it’s talking about warning off evil energy, it’s also turning that stuff into a positive. You’ll just have take a look at it yourself and tell me what you think when you get it.

S. Putnik: I feel like Devo, or the concepts of Devo, can go two ways. It could be really negative or it could be really hopeful and optimistic. And I feel like Mark’s artwork has this big sense of hope throughout all of it.

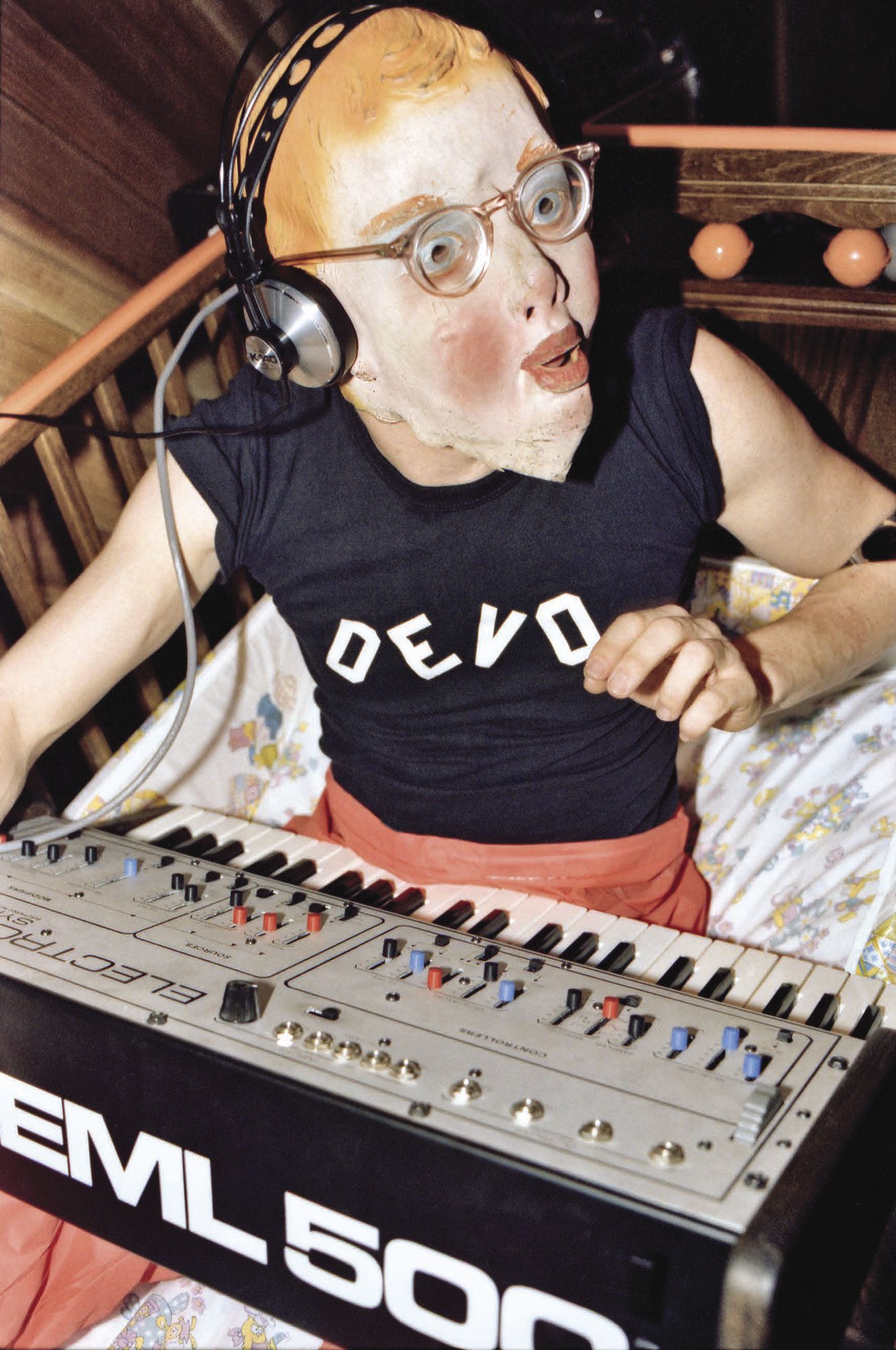

Mark: It’s the Booji Boy side.

Released by Blank Industries, Apotropaic Beatnik Graffiti features a bespoke black die cut hardcover book with embossed, spot varnished 3D eye relief plaque, debossed gold foil stamped lettering and gold gilded edge 115gsm matte art paper. A beauty for anyone’s coffee table or collection.

Limited copies of Apotropaic Beatnik Graffiti (w/ free limited edition exclusive flexi disc): are still available. Get your copy while supplies last.

See more of Mark’s work on his newly designed website and on Instagram.

Special thank you to Brent Broza for your photos of Mark at Beyond the Streets, a foreshadowing to the work in Apotropaic Beatnik Graffiti.

Brent Broza is an award winning photographer who grew up in Manhattan Beach surrounded by the Southern California beach community and culture. Surfing and skateboarding all over the famous South Bay with like-minded friends, Brent became very interested in art, sports and music at an early age. His passion of surfing and traveling have taken him all over the world. Learn more about Brent on his site.

Check out more of his work on his website | Instagram sites: Photos | Abstract | Paintings | Facebook | Twitter

Krysti Joméi is the co-owner and co-founder of Birdy Magazine. Creating in Colorado for the past decade plus, she’s lived all around San Francisco, by Houston’s NASA, on an island across from Seattle, near the WA/Canadian border, and under the Nandi Hills in Kenya. She loves outer space, the ocean, running in nature, anything written by Trent Reznor, and adventuring with her wolf dog and panther cat.

Jonny DeStefano is the co-owner and co-founder of Birdy Magazine. He is also the founder of the comedy activist space Deer Pile. His favorite color is red, and he loves shark attacks, hockey and upright bass.

Check out Mark’s February install, From the Postcard Diaries, or head to our Explore section to see more by this talented creative.

Pingback: Manuel of Omaha's Wild Kingdom by Jonny DeStefano and Michael David King - BIRDY MAGAZINE